| Competition | Played | Won | Drawn | Lost | For | Against |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| League | 210 | 90 | 49 | 71 | 362 | 320 |

| F.A. Cup | 7 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 8 | 16 |

| Total | 217 | 90 | 51 | 76 | 370 | 336 |

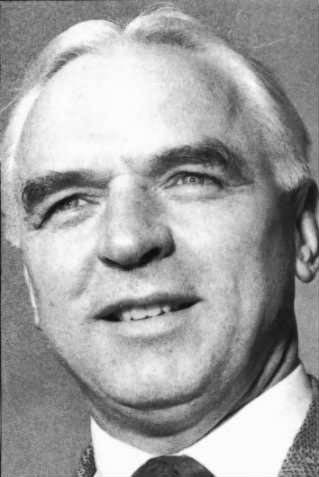

Tributes and Obituaries: Horatio Stratton Carter

John Simkin: Spartacus Educational September 1997 (updated August 2014).

Horatio (Raich) S. Carter (Inside Right) 5'8" 11st. Signed for Hull City on 15th June 1948. Native of Sunderland. Awarded four Caps as a schoolboy, two against Scotland in 1926-27 and 1927-28 and also played twice against wales in the same seasons. Signed professional for Sunderland in November 1931. Made debut at Hillsborough against Sheffield Wednesday in October 1932. Capped for England against Scotland at Wembley in 1934. Further caps before War against Hungary (2), Ireland, Scotland and Germany. Won F.A. Cup Medal in 1936-37 and scored over 100 goals between 1932 and 1939. He was trtansferred to Derby County in December 1945. gained further Cup Medal with Derby in 1945-46. Left for Hull City after 1947-48 season. he represented England on more than 30 occasions and Football League 5 times. Joined Hull as Player-Assistant Managerand became Player/Manager when Major Buckley left to join LUFC .

Horatio (Raich) Carter was born in Sunderland on 21st December 1913. He was the son of Robert Carter, who played for Port Vale, Fulham and Southampton before he suffered a serious head injury and was forced to retire in 1910 at the age of 29. As a young boy Carter was a fan of Sunderland and was a regular visitor to Roker Park. Carter's hero was Charlie Buchan, Sunderland's elegant inside-forward. Buchan also paid occasional visits to the Ocean Queen, the public house run by his father. Raich Carter was a talented sportsman and played football and cricket for his school in Hendon in Sunderland. In one match for his school he scored 111 runs in 25 minutes. Carter was even a better footballer and on 23rd April 1927, he played for England schoolboys against Wales. Carter, the smallest boy on the pitch, was only 13 years and four months old at the time. Also in the England team that day was Alf Young. Carter was a great success and he retained his place in the team the following year. Robert Carter, who had never fully recovered from his head injury, died on 14th March 1928. His wife, Clara Carter took over the running of the Ocean Queen. Ten days after the death of his father, Raich Carter played for England against Scotland. The Sunderland Echo reported that: "Young Carter, the Hendon schoolboy was, I am told, the best forward on the field in the match against Scotland on Saturday at Leicester which England won five to one." Carter's schoolboy international career was completed when he captained England against Wales at Swansea. He scored two goals in England's 3-2 victory. The Sunderland Echo reported: "This young Hendon product is one of the best all-round athletes Sunderland has produced for many a day, and his future career will be watched with interest." Carter left school at the age of fourteen. Johnny Cochrane, the manager of Sunderland, proposed that Raich should sign for the club as an amateur until he could sign professional at 17. Meantime he would be given a job in the club office. His uncle, Ted Carter, a detective sergeant in the local police force, instructed him to reject the offer and instead arranged for him to be apprenticed as an electrician with the Sunderland Forge and Electrical Company. When he reached the age of 17 a friend arranged for Carter to have a trial with Leicester City. On 27th December, 1930, Carter played at outside left for Leicester reserves against Watford. He had a poor game and Willie Orr, the Leicester manager, told him: "Son, you're too small to play football. You want to go home and build yourself up physically. Get some brawn and weight on you." Carter joined Esh Winning, who played in the Northern Amateur League. During the summer of 1931 he was invited by Clem Stephenson to join Huddersfield Town. However, he decided to accept the offer made by Johnny Cochrane, the manager of Sunderland. This included a £10 signing on fee, £3 per week plus £1 for a reserve team appearance. This was far better than the 9 shillings (45p) he was earning as an electrician. Sunderland's regular inside-left, Patsy Gallacher, was injured and could not play in the game against Blackburn Rovers on 21st October 1932. His place was given to local boy, Bob Gurney, but he developed influenza and Carter got his first game in the First Division of the Football League. Carter immediately struck up a promising partnership with left-winger Jimmy Connor. Carter retained his place in the side and he scored his first goal in the club's 7-4 victory over Bolton Wanderers. One reporter wrote: "Carter showed all the skill of a veteran and placed the ball with a deftness of a player twice his age to pave the way for practically every successful Sunderland move. He used the cross pass to find the opposite wing regularly and this lightening moving of the point of attack accounted for the early Bolton reverses." However, the Sunderland Echo argued that as Carter was only 18 years old he should not play in every game: "Carter is improving every time he turns out with the seniors. I think he should be brought on slowly and he should not be overworked. It is many years since I saw a more promising pure footballer." Despite this warning, Carter retained his place in the first-team. In December, 1932, Charlie Buchan, who was now a journalist, predicted that Carter would soon be playing for England. In the 1932-33 season Raich Carter made 29 cup and league appearances for Sunderland. As a regular member of the first-team his wages were increased to £8 a week. Club records show that the 19-year-old Raich was 5 feet 7 inches tall and weighed 9 stone 6 pounds. Carter won his first international cap for England against Scotland on 14th April, 1934. The England team included Eric Brook, Sammy Crooks, Cliff Bastin, Eddie Hapgood, Wilf Copping and Frank Moss. England won the game 3-0. He then went on a tour of Europe and played in the game against Hungary that England lost 2-1. In the 1934-35 season Sunderland finished as runners-up to Arsenal in the First Division of the Football League. The forward line included Carter, Patsy Gallacher, Bob Gurney and Jimmy Connor. According to Charlie Buchan Carter was the star of the Sunderland forward-line. He wrote: "His wonderful positional sense and beautifully timed passes made him the best forward of his generation." Despite only being 23 years old, Carter was made captain of the Sunderland team as a result of an injury to Alex Hastings. In the 1935-36 season Carter was in great form that season scoring 24 goals in his first 22 games and Sunderland built up a good lead in the championship. On 1st February 1936, Sunderland played Chelsea at Roker Park. According to newspaper reports it was a particularly ill-tempered game and Chelsea's Billy Mitchell, the Northern Ireland international wing-half, was sent off. The visiting forwards appeared to be targeting Jimmy Thorpe, the Sunderland goalkeeper, and he took a terrible battering during the match. After the game Thorpe was admitted to the local Monkwearmouth and Southwick Hospital suffering from broken ribs and a badly bruised head. James Thorpe died on 9th February, 1936. Sunderland was devastated by the death of their 22 year-old goalkeeper. However, they continued their good form and by 13th April, 1936, the club only needed to draw at Birmingham City to clinch the title. The result was a 7-2 victory. That season Sunderland became the first club to score over 100 goals in a season. Carter was joint top scorer with Bob Gurney with 31 goals. Carter's good form enabled him to regain his place in the England team. On 18th November, 1936, he won his fourth international cap against Northern Ireland. He also played in England's 6-0 victory over Hungary. The England team that day included Eric Brook, Sammy Crooks, Ted Drake, George Male and Alf Young. The following year he played in the England side that played Scotland. His wing partner that day was Stanley Matthews. However, the two men did not play well together and as a result Carter was dropped from the side. Tommy Lawton found the dropping of Carter inexplicable. "Raich was the perfect team man. He would send through pinpoint passes or be there for the nod down." Carter later explained why he never played well with Stanley Matthews: "He was so much of the star individualist that, though he was one of the best players of all time, he was not really a good footballer. When Stan gets the ball on the wing you don't know when it's coming back. He's an extraordinary difficult winger to play alongside." However, Stanley Matthews insisted that he loved playing with Carter: " I was on the right wing and inside me was local hero Raich Carter, who I felt was the ideal partner for me... Carter was a supreme entertainer who dodged, dribbled, twisted and turned, sending bewildered left-halves madly along false trails. Inside the penalty box with the ball at his feet and two or three defenders snapping at his ankles, he'd find the space to get a shot in at goal... Bewilderingly clever, constructive, lethal in front of goal, yet unselfish. Time and again he'd play the ball out wide to me and with such service I was in my element." In the 1936-37 season Sunderland could only finish 8th in the Football League. However, they had a great FA Cup run beating Luton Town (3-1), Swansea (3-0), Wolverhampton Wanderers (4-0) and Millwall (2-1) to reach the final against Preston North End. The monday before the cup final Carter married Rose Marsh. Immediately after the reception, Carter, along with his best man, Bob Gurney, left the bride and other guests to join up with their teammates at the Bushey Hall Hotel. The match took place on 1st May 1937. In the 38th minute, Hugh O'Donnellpassed to his brother, Frank O''Donnell, who scored the opening goal. Preston North End held the lead until early in the second-half. In the 52nd minute Eddie Burbanks took a corner. Carter headed the ball to Bob Gurney, who back-headed the ball into the net. Frank Garrick, the author of Raich Carter: The Biography, described what happened next: "In the 72nd minute, Raich Carter was given a chance to atone for his missed chance. He was in the inside-left position when a bouncing pass came over from Gurney to his right. Carter beat the fullback, raced the goalkeeper to the ball and lobbed it out of his reach into the net. Both players finished in a heap on the ground and Sunderland were in the lead. Carter was mobbed by his teammates and the cheering lasted for several minutes." Six minutes later, Patsy Gallacher created a third goal with a skilfully judged pass to Eddie Burbanks who shot home from a narrow angle. Carter had led Sunderland to its first FA Cup final victory. Sunderland players carry Raich Carter on their shoulders on 1st May 1937.Sunderland players carry Raich Carter on their shoulders on 1st May 1937. Tommy Lawton later explained: "Raich was the master of the pass which sneaks its way through the seemingly impregnable defence, but Raich was also an opportunist of the highest order. Yes, I know everyone knows all about his tremendous shot, but Raich had something else. He could size up a chance in a flash, and he would be on it before anyone could move. For instance, the centre forward has only to leap for a ball and nod it downwards and backwards, and Raich will be tearing in to ram the ball into the net." Stan Mortensen agreed: "Raich is a double-purpose inside-forward. He is clever and brainy enough to make openings for other players, and would be worth his place in any side for that alone. He also has the knack of cutting through for goals himself, and from the edge of the penalty area can hit a ball as hard as most." On the outbreak of the Second World War Carter joined the Sunderland Fire Service. This was a reserved occupation and his action was interpreted as being a tactic to avoid military service. As a result, Carter was often booed by the crowd in friendly games he played during the conflict. This caused Carter a great deal of stress and on 2nd October 1941 he joined the RAF. Like most professional footballers, Carter became a Physical Training Instructor, and did not see any action during the war. In 1945 Carter was transferred to Derby County. During his time at Sunderland he had scored 121 goals in 248 games. Carter formed an excellent partnership with Peter Doherty and in 1946 the club reached the final of the FA Cup. Doherty wrote: "He (Carter) was my twin, a brilliant schemer with a dangerous shot, with whom I was able to dovetail perfectly." Carter was also full of praise for his partner: "Peter Doherty was a perfect example of the true inside forward, combining the roles of both defender and attacker." The Derby Daily Evening Telegraph praised the efforts of Peter Doherty but added that "I regard Carter as the most valuable of the home forwards. It was he who undertook the scheming, acting as a one-man support of the front-line troops and keeping the opposing defence at full stretch by his shrewdly placed through passes." Derby County beat Charlton Athletic 4-1 in the final at Wembley. Carter therefore became the only man to have won winners' medals before and after the Second World War. Carter's fine form meant that he was selected to play in England against Northern Ireland on 28th September, 1946. Carter scored a goal in the first minute and England went on to win 7-2. Frank Swift, who played in goal that day, later commented: "Our team clicked from the start and the forwards were in magnificent form. Lawton led the line like the genius he is; Raich Carter did practically everything it is possible to do with a football - even to standing, foot on ball, as if marshalling his forces". Before the war Carter had played infrequently in the England team. Despite being in his thirties, Carter now established himself in what was considered by many to be an excellent England side and developed a fine partnership with Tom Finney. He played against the Republic of Ireland (1-0), Wales (3-0), Holland (8-2), Scotland (1-1) and France (3-0). Carter's England career came to an end with the shock 1-0 defeat against Switzerland on 18th May 1947. Now approaching 35, Carter was considered to be too old for international football. He had scored 7 goals in 13 games for his country. Carter continued to play well for Derby County and on 14th February, 1947, he scored four goals in the 5-1 victory over his old club, Sunderland. All told, Carter scored 34 goals in 63 games for Derby. In April 1948, Carter was transferred to Hull City for a fee of £6,000. A couple of weeks later Major Frank Buckley resigned and Carter became the player-manager of the club. Carter was an immediate success and that season Hull won the 1948-49 Division Three (North) Championship. Carter retired from playing football in 1951. During his time at Hull City he scored 57 goals in 136 games. He managed Cork Athletic before joining Leeds United in 1953. Leeds finished 2nd in the Second Division in the 1955-56 season but after two average seasons in the First Division, Carter resigned in 1958. Carter also managed Mansfield (1960-1963) and Middlesbrough (1963-1966). Raich Carter died in hospital in Hull on 9th October, 1994.

Sources

(1) The Sunderland Echo (24th April 1928) Young Carter, the Hendon schoolboy was, I am told, the best forward on the field in the match against Scotland on Saturday at Leicester which England won five to one.

(2) The Sunderland Echo (7th November 1932) Carter is improving every time he turns out with the seniors. I think he should be brought on slowly and he should not be overworked. It is many years since I saw a more promising pure footballer.

(3) Stanley Matthews, The Way It Was (2000) Roker Park was packed. I was on the right wing and inside me was local hero Raich Carter, who I felt was the ideal partner for me. Sunderland had a very talented team at the time and Carter was its mastermind. You would never have suspected, seeing him casually taking to the pitch, that here was a man who could lay claim to football genius. But he did and often. Carter was not a buzzing, workaholic inside-forward, far from it. At times you could be tricked into thinking he had only a passing interest in a game. He'd ghost into great positions and had that rarest of talents on receiving the ball; he could turn a game. `Let the ball do the work,' he'd say and how miraculously it did work when guided by his touches. His ball control appeared so casual and effortless it often passed unnoticed and seemed less a matter of conscious artistry than the possession of another sense. Raich Carter was a supreme entertainer who dodged, dribbled, twisted and turned, sending bewildered left-halves madly along false trails. Inside the penalty box with the ball at his feet and two or three defenders snapping at his ankles, he'd find the space to get a shot in at goal. "There's no such thing as a half chance,' he once told me. "They're all chances,' and how Carter could take them. He was stocky with hair turning silver, but he had the Midas touch on a football pitch turning many a game into a golden memory. In front of his home-town crowd, Carter put on a masterly show. Bewilderingly clever, constructive, lethal in front of goal, yet unselfish. Time and again he'd play the ball out wide to me and with such service I was in my element.

(4) Raich Carter, statement published in The Sunderland Echo (30th April 1937) I think we will win. I am proud to captain the Sunderland team in the final, and the finest wedding present I could possibly get would be to receive the cup from His Majesty tomorrow and to bring it to Sunderland on Monday. Sunderland expects, and our boys won't fail for the want of trying.

(5) Frank Garrick, Raich Carter (2003) From the kick-off it was clear that the players were suffering from nerves. In the opening exchanges passes regularly went astray. The Sunderland teamm took longer to settle down than Preston but gradually they came more into the game. Bob Gurney missed a difficult chance from an Eddie Burbanks cross and then put the ball in the net only to be judged offside. In the 38th minute, Frank O'Donnell combined with his brother Hugh, on the Preston left wing, to split the Sunderland defence and score the opening goal. This meant the Preston striker had scored in every round in the competition. More significant to Sunderland players and supporters was the knowledge that no team in a Wembley final had wonn the cup having conceded the first goal. However, this was the fourth time in five ties that Sunderland had fallen behind, so they knew they could come back. At half-time the score remained 1-0. In the dressing room one player claimed that O'Donnell must be stopped at alll costs. This provoked Raich Carter into a forceful response: "We have got to be more in the game. We have got to make the ball work more, find the man more. Let's play football as we can play it, and we shall be alright." It is interesting that there does not seem to have been any significant comment from the manager or the trainer. With the captain's words in their ears, the Sunderland team equalised within six minutes of the restart. Burbanks took a corner which Carter headed forward to Gurney who had his back to the goal and back-headed the ball into the net. This goal further revived the Sunderland players, confidence flowed and the football was transformed. Sunderland were really playing now and they laid siege to the Preston goal. Next Carter missed what the Echo described as "an absolute sitter" when, on receiving a pass from Burbanks, he topped his shot into the side netting. The moan from around the stadium reinforced Carter's sense of disappointment. A chance had come and he had missed it. At the other end of the pitch one of the great battles of the match between Sunderland's centre-half Bert Johnston and the Preston number nine O'Donnell continued to rage. Johnston had only prevented his opponent from scoring a second goal by bringing him down. The referee administered a stern warning but no caution or dismissal as would be the case today. As the duel continued Johnston gradually achieved mastery. At the same time Charlie Thomson, in midfield for Sunderland, was playing more and more impressively. He gave support to the defence and was involved in the moves which led to the goals. In the 72nd minute, Raich Carter was given a chance to atone for his missed chance. He was in the inside-left position when a bouncing pass came over from Gurney to his right. Carter beat the fullback, raced the goalkeeper to the ball and lobbed it out of his reach into the net. Both players finished in a heap on the ground and Sunderland were in the lead. Carter was mobbed by his teammates and the cheering lasted for several minutes. Choruses of the song "Blaydon Races" echoed around the stadium.

(6) Michael Parkinson, Football Daft (1968) Raich Carter strode alone on to the field some time after the other players, as if disdaining their company, as if to underline that his special qualities were worthy of a separate entrance... It seemed that he treated the crowd and the game with massive disdain, as if the whole affair was far beneath his dignity. He showed only one speck of interest in the proceedings, but it was decisive. He was about 30 yards from the Barnsley goal and with his back to it, when he received a fast, wild cross. He killed it in mid-air with his right foot and hit an alarming left-foot volley into the roof of the Barnsley goal. Carter didn't wait to see where the ball had gone. He knew. He continued to spin through 180 degrees and strolled back to the halfway line as if nothing had happened. Normally the Barnsley crowd greeted any goal by the opposition with a loud silence, but as Carter reached the halfway line a rare thing happened: someone shouted, "I wish we'd get 11 like thee, Carter lad." The great player allowed himself a thin smile, as well he might, for he never received a greater accolade than that.

(7) Arthur Appleton, Hotbed of Soccer (1960) In 1960, Arthur Appleton in his book Hotbed of Soccer wrote that, "before the War Sunderland fans had, in the main, been slow to value Carter at his true worth, partly because he had developed with other excellent players ... although he was a local boy he was not generally taken to heart mainly, I think, because of his impassive demeanour. His efficiency as a footballer, although recognised by quite a few, was not fully appreciated until he had left - and really emerged as a national figure - during and immediately after the War. Carter was Sunderland's most consistently effective inside forward since Buchan.

(8) Tom Finney, My Autobiography (2003) But nothing that occurred during the first few weeks - and most of it was good - could have prepared us for the events of 6th December and the visit of Derby County, locked with us in third place. That fixture always had the makings of a tasty game but this time it produced what can only be described as a match-of-a-lifetime. Many Deepdale diehards still rate it as the best they have seen and I wouldn't argue. The Rams were a talented team and their talisman, Raich Carter, was a superstar in every sense of the word. They hit us like a whirlwind; mentally, some of our lads were still in the dressing room as Derby eased into a two goal lead, fashioned by the mesmerising Carter. We looked at one another and faced up to the options. Either we carried on in our disjointed state and faced a humiliation or we got stuck in and launched a fight back.

(9) Tommy Lawton, My Twenty Years of Soccer (1955) Raich Carter was another great inside forward. Raich was the master of the pass which sneaks its way through the seemingly impregnable defence, but Raich was also an opportunist of the highest order. Yes, I know everyone knows all about his tremendous shot, but Raich had something else. He could size up a chance in a flash, and he would be on it before anyone could move. For instance, the centre forward has only to leap for a ball and nod it downwards and backwards, and Raich will be tearing in to ram the ball into the net.

(10) Stanley Matthews, The Way It Was (2000) I was playing in a game for Blackpool against Derby County. The rain was coming down like stair rods and the Bloomfield Road pitch was a quagmire. Carter was an England team-mate but I remember thinking he just wasn't up for it that day. With about five minutes remaining and the score 0-0, Derby won a corner. As the Derby players trundled into our penalty box, Harry Johnston went across to mark Carter who had taken up a position just outside the angle of the six-yard box, nearest to where the corner was being taken from. Carter stood facing the Derby winger who was taking the corner with his hands on his hips. Whenever I saw a player do that I always took it as a sign that he was banjaxed, had lost interest in the game, or both. There was an eerie silence in the ground as the Derby player prepared to take the corner. Suddenly it was broken by a booming voice from the terracing behind our goal. "Go home Carter! You're washed up and finished!" Even though he was an opponent of the day, I remember thinking it was a cruel thing to say. True, Raich was a great player, but on this particular day he had done nothing and the cruel shout at Carter's expense seemed to have a certain ring of truth to it. I felt sorry for him. The corner was played in to where Carter was standing and it reached him at chest height. With a sudden but slight backward step, he cushioned the ball with his chest and it fell dead at his feet. With lightning speed, as if part of the same movement, he swivelled and with the ball at knee height hit a thunderbolt of a volley. Our goalkeeper 'Robbo' Robinson didn't have time to react and stood motionless, able only to feel the draught the ball created as it flashed past him. The far corner of the net bulged into the shape of an elbow and the ground was stunned into such a silence I actually heard the swish of the ball as it cut a furrow down the rain-soaked net to the ground. For a few seconds, the absolute silence among the rainsoaked crowd continued; then the same booming voice came from behind our goal. "All right then, but you're not as good as you used to be!"

(11) Stan Mortensen, Football is My Game (1949) Carter, whose career began with Sunderland, continued with Derby County, and looks like concluding with Hull City... but if you observe him closely on the field, you will see that he is blessed with a pair of strong legs. Trainers usually say first: "Let's look at the thighs". Carter has it there, and his deep knowledge of the game enables him to skip clear of a lot of trouble. Raich is a double-purpose inside-forward. He is clever and brainy enough to make openings for other players, and would be worth his place in any side for that alone. He also has the knack of cutting through for goals himself, and from the edge of the penalty area can hit a ball as hard as most. When he was with Sunderland he won a Cup medal in 1937; he moved on to Derby, and was on the winning side in the first post-war final against Charlton Athletic. When he was signed as player-manager for Hull City his immediate job was to try to gain promotion for them.

Remembering Raich: The Story of the Silver Fox: Amber Nectar | The Soul of Hull City #9: Raich Carter

Raich Carter, like so many of his great contemporaries, may not be a household name today, but to those who witnessed him in action, Carter lives long in the memory. Cruelly stripped of the chance to play during his finest years due to the war effort, Carter is the only man who can hold acclaim to having won an FA Cup before and after the war. An exceptional sportsman, Carter was not content as one of England’s finest footballers and also played County Championship Cricket for Derbyshire.Beginning his career in 1931 for Sunderland, at the age of 18, Carter went on to represent the club 245 times, scoring 118 goals in the process. In 1936, still only 23, Carter became the youngest man to ever captain a side to a league title as Sunderland became Football League Champions in the 1935/36 season. Within a year, he had added the FA Cup to his list of honours, scoring in the Black Cats 3-1 defeat of Preston North End. The complete footballer, Carter was not an out-and- out striker but rather an inside-forward who contributed to multiple phases of play. Both a creator and converter of chances, Carter was likened to Paul Scholes in his prime at Manchester United by biographer Frank Garrick. Despite his midfield duties, Carter was Sunderland’s joint top scorer in their Championship winning season. The Mackems put an end to Arsenal’s First Division dominance, the North Londoners had won the last three league titles and it would take a special team to stop them adding another in 1936, Leading the league, Sunderland faced the defending champions in a crucial game; in the quest to prove their title credentials at Roker Park, it was Carter who spearheaded a famous Sunderland victory, scoring a hat-trick in a 5-4 win. The victory gave Sunderland a seven point lead at the top of the table, a lead they would not let slip. It would be Carter once more who led Sunderland to victory in the Community Shield, against Arsenal once more, scoring a last minute winner. The title win had been Sunderland’s sixth, but one competition which continued to elude them was the FA Cup. This became priority number one in many respects the following season. Sunderland reached the final which was to be played against Preston North End at Wembley, the game would prove a fitting conclusion to a fine few weeks for Carter. He had just married his wife and played his finest game for England against Scotland in front of 149,693 people. So good was Carter’s performance, executives from Madame Tussauds met with Carter to arrange a waxwork of him, despite his tender age of 24. In the final, the Silver Fox did not disappoint, assisting twice and scoring once as Sunderland came back from a goal down to win 3-1. Carter received Sunderland’s first FA Cup trophy as captain from the Queen in the coronation year of 1937. As the Second World War commenced in 1939, Carter was aged 26 and embarking upon the peak of his career. Whilst wartime football did continue it was unrecognisable from peacetime football. The national league, FA Cup and international caps all ceased to exist for roughly six years. By the time football returned in it’s recognisable form, Carter was almost 32. Sunderland were keen to build their post-war team around him but with his wife suffering poor health and having lost six years of his career, Carter needed the security of a long and rewarding contract. Sunderland were unwilling to meet his demands and Carter transferred to Derby County for £8,000. Despite being an almost unheard of fee for a player on the wrong side of 30 at the time, Carter, never lacking confidence, said of the deal “Sunderland were silly to sell me for that price and Derby were lucky to get me.” Instant success would come his way with the Rams, and Carter found himself back at Wembley for the 1946 FA Cup final. For Carter, now an experienced pro who had won almost every domestic trophy and played for England at Wembley on numerous occasions, the game lacked the novelty of his Sunderland cup final. The novelty was replaced by an assured confidence. Interviewed after the game, teammate Reg Harrison declared, “I knew we’d win the cup because Raich said so.” His confidence rubbed off on the rest of the Derby team and an attacking Charlton side made for a thrilling encounter, but one in which the Rams always had the edge and ran out comfortable 4-1 victors to make Carter the only footballer to ever win an FA Cup before and after the Second World War. Raich would never be drawn on comparisons between his time with Derby and hometown club Sunderland, but he certainly enjoyed his time in Derbyshire where he went on another cup run two years later without managing to lift the trophy and also starred for Derbyshire in county cricket. A right handed batsman, he played for Derbyshire in 1946 and later appeared for Durham in the Minor Counties Championship. Carter’s cricket experience was limited before the war, but in 1946 he was asked to play for Derbyshire’s second team. He top-scored with 47 against Notts’ second team and was asked to play professionally, Carter accepted the offer. Raich played just three First Class matches for Derbyshire, as his lack of experience was exposed when batting against top class bowlers. He admitted his lack of judgement in bat, and found the longer sessions, which he had not been used to, exhausting. As a bowler, Carter never looked out of place. He took two wickets for 39, showing his natural ability, but at 32, he was too old to iron out the deficiencies in his batting. After this, Carter only played for Derbyshire in benefit matches, although he did turn out for local side Chaddesden and briefly for Durham. Over 3,000 people turned out to watch his 49 runs against Duffield in the semi-final of the Mayor’s Hospital Cup. A pulled muscle ruled Carter out of the final, which Chaddesden lost to Rolls-Royce without their star man. At the age of 35, with little career prospects outside of the game, Carter was keen to make the move into management and it became clear that this role would have to be away from Derby. He was awash with offers; Notts County, Leeds United, Nottingham Forest and Hull City were all very keen on acquiring his services. Still regarded as one of the finest players in the English game there was shock when Carter chose Third Division Hull City as his next destination. Carter himself had worried about making such a drop but was drawn by the ambition of the Hull directors and current manager Major Frank Buckley. The Tigers paid £6,000 for Carter to become player/assistant manager and serve as the understudy to Buckley. Major Frank Buckley was a veteran of the game who had been very successful at Blackpool and Wolves, and his influence within the game, particularly upon Sir Matt Busby, Bill Shankly and Brian Clough, is still spoken about today. The signing was a huge coup for Hull and when Carter entered East Yorkshire, he saw posters all around the city advertising the weekend’s game against York, simply declaring “Carter Will Play.” Such was the talk and hype surrounding him, Carter admitted to feeling a nervousness he had not felt since his days at Sunderland when he took to the field at Boothferry Park for the first time. Shortly after his Hull City debut, Buckley resigned and it became clear Carter would soon become the new first team manager despite little to no experience. In the same year Carter played his last game for England, in an international career spanning over 13 years. The second longest at the time and still the eleventh longest today of any England player. Carter was given full control and hopes were high in East Yorkshire for the forthcoming season. With each game, a record attendance seemed to be set at Boothferry Park as the Tigers looked to get out of the Third Division, and Carter continued to show his class on the pitch. Such was the excitement surrounding him in the Third Division, opposition fans were even known to greet and celebrate his arrival at their grounds. By Christmas, the Tigers were going strong in the league, enjoying a cup run, seeing regular attendances just shy of 50,000. Hull City drew Manchester United in the sixth round of the FA Cup and the demand for tickets was phenomenal. An official crowd of 55,019, still a Hull City record, was recorded with over 10,000 letters to the club from fans not even opened. Fearful of Carter, Manchester United tried to mark him out of the game but struggled to overcome the Third Division side, needing a 73rd minute controversial goal to go through 1-0. Despite defeat, the performance had given Hull and Carter national acclaim and respect, which was surmounted by promotion at the end of the season despite testing fixture congestion. He went on to establish Hull in the Second Division before retiring and going on to manage Cork, Leeds, Mansfield and Middlesbrough. After full retirement from management, Carter moved back to East Yorkshire where he remained until his death in 1994 at the age of 80. His legacy lives on, the Silver Fox is still talked about in the three city’s who were graced with his remarkable talent. In Sunderland, there is a sports centre named the Raich Carter Sports Centre in his honour, whilst in Hull he has a road named after him and the first ever game at Hull’s KC Stadium between Hull and Sunderland was played for the Raich Carter Trophy.

Hero – Raich Carter: Heroes & Villains:by Les: March 1, 2010:

Horatio Stratton Carter. The past few years may have skewed things slightly, but even after our first ever promotion to the top flight, after Okocha, Ashbee, Windass, Barmby, Turner, Geo, Huddlestone, Aluko, Elmohamady, Chester, after 60 subsequent years of good and bad, Raich is still talked about in hallowed terms by football fans in Hull. And Derby. And Sunderland. Raich would walk into the greatest XIs of any of the three teams he graced in England at inside left or inside right. Had the war not punctuated his career when he was at his most productive, he’d have more than a few supporters for a role in an all-time England XI too. Born in Hendon, a ship-building area of Sunderland (his ‘posh’ Christian name was from his grandfather, Stratton his mother’s maiden name), in 1913, Carter was a prodigious youth sportsman. It was football, however, that had Raich marked out as a star from an early age, following in the footsteps of his father, who had played for Port Vale, Fulham and Southampton. An England schoolboy international, despite his slender build, Carter was fast-tracked into the Sunderland first team aged 18, and didn’t look back…By the time he had reached his mid-20s he had a championship medal, had won the FA Cup (scoring in the final) and was establishing himself in the national team. By 1939, he was regarded as one of the finest players in the country, and at the age of 26 was just beginning to stamp his authority on the world of international football. Then Hitler went and invaded Poland…Upon war being declared, Raich joined the fire brigade – a decision that didn’t go down too well with many. Though this enabled Raich to continue playing for Sunderland in their war-time games, as well as guesting for various other teams in the region in fund-raising games for the war effort, his lack of military action disappointed many fans, despite the fact he was spending most of his time extinguishing the fires caused by the ceaseless bombing of Sunderland’s shipyards by the Luftwaffe. Sensitive to this, Raich signed up with the RAF, and was eventually posted in Loughborough in a fitness and rehabilitation role. This allowed him to settle in Derby, near his wife’s family, and occasionally guest for the town’s football team. He would also play 17 times for ‘England’ during the war, scoring 18 goals – second only to Tommy Lawton’s 24. Upon the end of the war, Raich’s disillusionment with the regime at Sunderland, and his enjoyment of his time in Derbyshire, saw him move to Derby County. Almost immediately he led his new team to the FA Cup, making him the only man to win the trophy before and after the war. The England call-ups continued and Raich continued where he’d left off in 1939, maintaining his reputation as one of the most skilful and entertaining players in the country. He also played a handful of times for Derbyshire in cricket’s County Championship, though his impressive club batting was soon found out by the county bowlers. You don’t care about any of that shit though. In 1948, Raich was looking for a move into management. Assistant management offers flowed in, with two, Division Three North Hull City and Division Two Nottingham Forest, emerging as frontrunners. Mindful of the fact that City manager Major Frank Buckley was nearing retirement age, and Forest manager Billy Walker was relatively young in management terms, Raich plumped for East Yorkshire, £6,000 was exchanged and a legend was created. On April 3rd 1948, Raich led out his new teammates against York City in front of 33,000 at Boothferry Park. The game finished 1-1, and afterwards Raich immediately travelled up to Scotland to fulfil his duties as England reserve in a friendly at Hampden Park. In the match, England keeper Frank Swift went off injured, but sadly the substitution law that was being experimented with at the time was not being used for the friendly, so instead of creating Hull City history by becoming the club’s first England international, Raich accompanied Swift to Glasgow’s Victoria Hospital. So near, yet so far…While Raich was away, his decision to join opt for City because of the potential for a quicker move into full management was proven to be a shrewd one. Major Buckley had fallen out with the City board, resigned, and Carter was offered the job one game into his City career, a move made official on April 23rd. In the following summer, Carter signed former Sunderland FA Cup final teammate Eddie Burbanks to add to an impressive-looking team that contained the likes of Billy Bly, Ken Harrison, Norman Moore and Jimmy Greenhalgh. City got off to a flyer that year, with Raich prompting from inside left and Boothferry Park regularly packing in 30,000-plus gates. The side remained unbeaten until October 16 when Darlington won 1-0 at Boothferry Park. Carter responded by signing Danish international and City legend-in-the-making Viggo Jensen. They weren’t to lose again until mid-February, in which time First Division Stoke had been knocked out of the FA Cup in the fifth round in a match at the Victoria Ground. City were the talk of the football world, with Carter’s profile remaining as high as it had been when he was playing in the top-flight. His presence was adding thousands to any game he played in. Though clinching promotion was not quite a formality, the sixth-round tie at home to Manchester United in the FA Cup in 1949 captured the city’s, and nation’s, imagination in a way that that other sport could only dream of. You should all know the attendance that day (55,019 for those of you who were too cool as children to spend hour upon hour studying the facts and figures in your Rothmans) and that City lost 1-0. Unluckily too, by most accounts, with the ball reportedly going out of play just before Manchester United scored the game’s solitary goal. Raich played left wing that game, and was largely subdued by Harry Cockburn, but his managerial qualities were there for all to see. City were matching the best teams in the land under his stewardship. It seemed that under Raich, it was a matter of when, not if, First Division football would finally come to Hull. Promotion to Division Two was sealed on April 30th after a 6-1 win at home to Stockport, with Carter netting twice. In the whole season, Raich had missed only three league games, scoring 14 times (level with Viggo Jensen and only behind centre-forward Moore’s 22). Football historian Peter Jeffs names Raich as the manager of the year in his ‘The Golden Age of Football’. Raich was the king of Hull. The city that had taken such a battering in the war – and had been largely been ignored by the national media – was given reasons to be both cheerful and optimistic. And it was Raich we had to thank. So, Division Two beckoned. City had shown that we could match the best in the FA Cup the previous year, but could we sustain it over a full season? Did Raich’s 36-year-old legs have another full season in them? Would he be as effective at this level? Of course he would. City won 12 of the first 18 games of the season to challenge at the top of the table, with Raich scoring 13 times. Don Revie was signed to strengthen the midfield for what was then staggering fee of £20,000. However, Revie proved to be a disappointment, and the wheels started to come off City’s season. Carter missed only three games all season, but was to only score three more times and a once-promising campaign faded as City won only one of the final 15 games, and finished what was generally viewed as a disappointing seventh. In the eyes of the City faithful, however, Carter could still do no wrong. The attendances still touched 50,000 for some home games, and Carter’s performances had many in the national press touting him as a potential member for England’s World Cup squad in Brazil. As if to prove those pressmen right, Raich started the 1950-51 season in incredible form, scoring in eight of City’s first nine games as the Tigers once again started a season among the division’s front-runners. However, an injury to Raich in November saw the good form tail off, and though it picked up again on Raich’s return (which helped see off top-flight Everton in the third round of the FA Cup, a game in which Carter scored and Boothferry Halt was first used), the gap to the top two couldn’t be breached and City had to settle for 10th. Yet again, there’d been plenty of cause for optimism, but how much longer could Carter go on for? And who could replace him on the pitch? His 35 appearances had brought with them 21 goals. Alf Ackerman and Syd Gerrie had been brought in to plug the goalscoring gap with some success, but replacing the irreplaceable? You might as well replace Michael Turner with Ibrahima Sonko. The 1951/52 season started with the usual optimism. Though Raich had missed the team’s pre-season tour to Spain to care for his sick wife, he’d declared himself fit for another season. However, he was injured in the first game of the season – a goalless draw against Barnsley. Little did anyone know that it was to be his last game as City’s player manager. Carter handed in his resignation on September 5th, and it was unanimously accepted by board on September 12th. Mystery shrouded Raich’s resignation. The board said nothing, and Raich’s vague explanation was that he’d quit because of “a disagreement on matters of a general nature in the conduct of the club’s affairs”. And now for the tricky bit. Does a writer risk sullying the name of one of the greatest players in the club’s history by referring to what was largely believed by City fans at the time the reason for Carter’s departure? Or does one gloss over it as irrelevant gossip. Ah, you’ll just have to forgive me, but it was widely accepted around the city that Carter had become romantically entangled with a female member of the staff at the club (often rumoured to be a board member’s wife). A few years later, Raich’s first wife, Rose, died tragically young, aged only 38, after years of ill health. He was later to marry former Hull City employee Patricia Dixon. What actually went on when Raich left the club has been subject to decades of speculation. I don’t know what happened. All I know is that none of it should in any way detract from Raich’s outstanding contribution to the club and football in general, and that the ultimate losers in all of this were Hull City. Raich made clear his intention to go back into management, and while awaiting the right offer, he opened a tobacconists on George Street. However, without Raich, City were rudderless. A 12-match winless run saw the board partially relent and allow Raich to return – as a player. The club’s fortunes improved with Raich dictating things, and the club staved off the relegation that once looked to be a certainty. The club even had time to beat First Division Manchester United 2-0 at Old Trafford in the third round of the FA Cup. Carter was man of the match. In the final game of the season – in what was to be Raich’s final game in the black and amber – Doncaster were beaten 1-0. The scorer? One Horatio Stratton Carter. At the end of the season, Carter was given a civic testimonial by the Lord Mayor of Hull and the Carter family were showered with gifts from all kinds of companies and families connected with Hull. But the bitter truth was that Raich was going to move on, and when he did, it was surprisingly to Cork Athletic, who offered him a lucrative contract to play for them. After leading the team to the Irish Cup, managerial offers flooded in for Raich back in England. He opted for Leeds, where he would again follow in the footsteps of Major Frank Buckley, and also help shape the early stages of the career of John Charles. After getting Leeds promoted to Division One, Raich resigned from Leeds in circumstances clearer than his initial departure from City. He couldn’t recover from the board selling John Charles to Juventus. Managerial posts at Mansfield (where he oversaw the early stages of the career of Ken Wagstaff) and Middlesbrough followed, but Raich’s managerial career, while impressive in places, was never to hit the heights of his playing days. After his sacking by Middlesbrough, Raich moved back to Willerby and made ends meet by starting his own football magazine, reporting on matches for the Daily Mirror, sitting on the pools panel and opening a newsagents close to where the KC is now situated. He remained a regular at Boothferry Park with his son, Raich Jr, but sadly only as a commendably passionate supporter. Raich’s final ‘appearance’ at Boothferry Park came at half time in an otherwise forgettable 0-0 draw against Sunderland in October 1988. He and fellow Sunderland FA Cup final hero Bob Gurney dribbled a ball up and down the pitch as the crowd – to a man – stood to applaud them. The affection for Raich from all supporters was clear for anyone to see, several decades after he’d had any involvement with either club. Raich died on October 9th, 1994 in Hull. At the time largely regarded as the club’s greatest ever player, the city mourned one of its finest adopted sons. At the request of then chairman Martin Fish, the funeral cortege stopped outside Boothferry Park to be met by a guard of honour formed by the playing and management staff and some 400 fans. His funeral ceremony was littered with football greats mourning a player who could stand shoulder to shoulder with any of them. So where does Raich stand in what we can now hopefully call with some justification the ‘pantheon’ of City greats? Comparing players from different eras is in many ways futile. Who was the best Hull City player out of Carter, Waggy, Chillo, Whittle, Ashbee, Windass, Turner, Chester, Huddlestone et all? Only a handful of them have thrived in the top-flight with the club, but that shouldn’t necessarily end the argument. Raich’s stats – 136 games, 57 goals – don’t necessarily tell the full story either, the story of the hope he gave a bomb-battered city and its underperforming football club, the flashes of skill that could change a game, the cheeky penalties where he would pass the ball to a teammate instead of shooting, the fact that one of the country’s finest players was gracing the black and amber. Raich’s name is remembered with a sports centre in his home town, a road in the Kingswood area of Hull, and a trophy that we played Sunderland for in the opening of the KC. More importantly, it is stamped all over the history of the teams he played for. ‘Carter the Unforgettable’ was the slogan printed on t-shirts by fanzine Hull, Hell and Happiness in the early 90s. Given that he could still inspire such affection from a club for whom he hadn’t played for in several decades, that would seem to be a most fitting epitaph.

Obituary: Raich Carter: Tuesday 11 October 1994: The Independent

Horatio Stratton Carter, footballer: born Sunderland 21 December 1913; played for Sunderland, 1931-45, Derby County 1945-48, Hull City 1948-52, Cork Athletic 1953; capped 13 times for England 1934-47; manager, Hull City 1948-52, Leeds United 1953-58, Mansfield Town 1960-63, Middlesbrough 1963-66; married (one son, two daughters); died Willerby, Humberside 9 October 1994. RAICH CARTER, 'The Great Horatio', was by common consent the finest English inside-forward of his generation. But for the Second World War which sliced his footballing career in two, he would have won many more than his 13 full international caps, though that relatively meagre total - relative, that is, to his immense talent - might have had a bit to do with an impatient, abrasive side to his character. Carter was that rare being, a magnificent maker and taker of goals, and were he playing today his transfer valuation would surely be astronomical. During his peak years and beyond, when his black hair had turned prematurely to a distinguished silver, he cut an imperious figure, radiating self-confidence as he strutted around the pitch, invariably dictating the course of a game. Some would (and did) call him arrogant, but there was no denying the Carter class. He shot thunderously with either foot, especially his left; his ball control was impeccable and his body-swerve little short of sublime; and, crucially, he possessed the intelligence to put these natural gifts to maximum use. The Wearsider Raich, the son of a professional footballer, exuded all-round sporting ability from an early age, his magnificent athleticism making light of a lack of physical stature. By 1927 he was playing for England Schoolboys and in 1930 he joined Leicester City on trial, only to be released because he was 'too small'. His home town club, Sunderland, had no such qualms, and earlier thoughts of an engineering career were jettisoned as he progressed rapidly to first-team status. Thereafter Carter's rise became positively meteoric. In 1934 he made his full England debut, against Scotland at Wembley; two years on he inspired an essentially ordinary Sunderland team to the League championship, becoming the youngest title-winning skipper in the process; in 1937 he was the star turn as the Rokerites beat Preston North End to lift the FA Cup. Thus, at 23, Raich Carter had won every honour then available to a footballer. Nevertheless, his international appearances were spasmodic and it was not until 1943, when that other splendid inside-forward Wilf Mannion was drafted into the army, that Carter was recalled to the England side on anything like a regular basis. Having joined the RAF and been stationed at a pilot rehabilitation centre at Loughborough, it was convenient for Carter to guest for nearby Derby County while the conflict continued, and when peace resumed the Rams had seen enough of him to make the arrangement permanent. Accordingly they paid some pounds 8,000 for his services, a transaction of which Carter, not a man renowned for false modesty, remarked later: 'Sunderland were silly to sell me and Derby were lucky to get me.' At the Baseball Ground, he linked up with the brilliant Irishman Peter Doherty, and together they helped Derby win the first post-war FA Cup Final. That same year, 1946, Carter furnished further proof of his all-round prowess by appearing in three first-class cricket matches for Derbyshire and might have flourished in the summer game but for his football commitments. As it was, having won his last cap in 1947 at the age of 33, he moved to comparatively humble Hull City for a pounds 6,000 fee in 1948, initially as player/assistant boss but within a month as fully fledged player/manager. A year later, while still taking an active part on the pitch - 'I am determined to play on as long as I can raise a gallop,' he said - he led his charges to the Third Division (North) championship, and what seemed likely to be a successful management career was underway. Carter upset some followers when he declared: 'My aim is to play high-class football and let the result take care of itself.' But his acquisition of high-quality performers such as Neil Franklin and Don Revie signalled that he would not be content to linger idealistically in the Second Division. However, having not achieved the promotion he had expected, Carter ever the perfectionist, resigned in September 1951. He returned for the second half of the season as a player only, showing much of his old flair, and when he made his final Football League appearance that spring he had scored 216 goals in 451 outings. Those creative feet were still itchy, however, and in 1953, his 40th year, he spent half a season with Cork Athletic, helping them to win the Irish equivalent of the FA Cup. Clearly Carter had more to contribute and later that year he took over the reins of Leeds United, guiding them to promotion to the top flight in 1956. Nevertheless, his intolerance of lesser talents rustled plenty of feathers at Elland Road and after his best player, John Charles, had departed for Italy, results declined and he was dismissed. Come 1960 Carter was back in circulation as manager of Mansfield Town, whom he led out of the Fourth Division in 1963, after he which he moved up to Middlesbrough. Sadly, at Ayrsome Park he experienced the leanest time of his life in soccer and with the club on the brink of relegation to the Third Division, he was sacked in 1966. Thereafter Carter worked in the sports department of a Hull store and then ran a business in the town before retiring to nearby Willerby, suffering a severe stroke last year. During his latter years he was disdainful of modern trends in the game, but once, looking back, he admitted there could be no finer life than a footballer's. He could have added, with truth, that there had been few finer footballers than he.

Vintage Footballers : Raich Carter

Forward Horatio “Raich” Carter was one of the true greats of the football world to have come out of the 1930s. Born in Sunderland in 1913, son of a former professional footballer, Robert Carter, who had played for Port Vale, Fulham and Southampton, he signed for Sunderland as an amateur in November 1930, signing professional a year later and making his debut at Hillsbrough against Sheffield Wednesday in October 1932. Already club captain, he scored 31 goals in 39 games as Sunderland won the League Championship in 1936 (after being runners up the year before), scoring the winner the following year at Wembley in the FA Cup Final as Sunderland beat Preston North End 3-1. First capped for England in April 1934 against Scotland, he went on to win 13 caps either side of WW2, scoring 7 times, his final cap coming against Switzerland in May 1947. He also made 8 wartime appearances for England. In December 1945 Sunderland sold him to Derby County for £8000 after 131 goals in 281 games, and he immediately won the 1946 FA Cup with Derby scoring 12 goals in the cup run but none in the Final itself which Derby won 4-1 after extra time against Charlton. He scored 50 goals in 83 games for The Rams. In March 1948 Hull City paid £6000 to get Carter and 4 weeks later he was installed as player manager winning the Division 3 (North) Championship in 1949. He resigned as manager in September 1951 but continued to play for The Tigers until April 1952, scoring 62 goals in 150 appearances. In 1953 he had a short spell as player manager of Cork Athletic in Ireland before becoming manager of Leeds United that year, taking them to promotion in 1956 with John Charles at the centre of his team. He left the club in 1958 but returned to management in 1960 with Mansfield Town, staying 3 years before taking over at Middlesbrough, a spell which lasted a further three years. He also played 3 first class cricket matches for Derbyshire.