| |

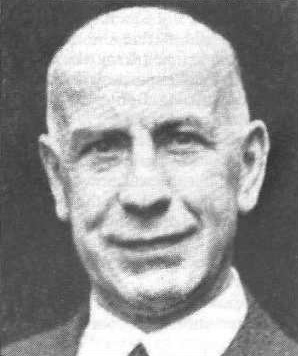

Buckley: Franklin Charles (Major/Frank)

1948-1953

(Manager Details)

(Manager Details)

Buckley was born in Urmston, Manchester on 9th November 1882,and his brother Chris Buckley

played with Aston Villa, which was also his first football club. He joined the Army but

bought himself out and signed for Villa in 1904 but never played for their first team. He

moved to Non-League Brighton & Hove Albion before returning to the First Division with

Manchester United in 1906. He only played three League games before he moved across the city

to Maine Road and joined the "Sky Blues" of Manchester City playing seven games in the

1907/08 season and managed only four games the following season before joining Second

Division Birmingham City. There he was a regular and played fifty-five League matches in the

next two seasons, and scored four goals. He moved across the Midlands to Second Division

Derby County for the start of the 1911/12 season and played twenty-eight games and scored

once as the Rams gained promotion to Division One. He gained his only England cap while at

the Baseball Ground when he played for his country in a surprise 3-0 defeat by Ireland at

Ayresome Park, Middlesbrough in 1914. He stayed until the end of the 1913/14, playing a

total of ninety-two League games and notching three goals before Derby were relegated and he

joined First Division Bradford City but only played four League games for the Yorkshire side

before Worl War One curtailed their association. Buckley enlisted with the 17th Middlesex

Regiment, where he commanded "the Footballers’ Battalion". He saw action and received wounds

to his lung and shoulder in the Battle of the Somme and rose to the rank of Major. On his

return, he joined Non-League Norwich City and was appointed Manager. The Canaries had been

so debt-ridden that the receivers had wound the club up, but following an extraordinary

general meeting, the club was resurrected and Buckley was placed in charge in February 1919

and returned the club to Southern League football. His stay was short and he left in July

1920 he was gone as financial disputes brought wholesale changes of personnel. He then spent

some time as a commercial traveller. Buckley became the first version of the modern football

Manager, not content to settle for the Manager/Secretary which had been normal before him.

He believed in encoraging the production of players by the club rather than buying success

as most of the successful clubs had done before him. He encouraged the use of young players

reared by the club and bought and sold players judiciously to ensure that the club always

ran at a healthy profit. On 6th October 1923, the Directors of Second Division Blackpool

appointed him as their new Manager. He stayed at Blackpool for four years and there is no

doubt that his shrewd managership greatly assisted the advancement of the club. He was also

innovative and change the Blackpool colours to the famous tangerine. Although they never

gained promotion, he set up the Blackpool Youth system and scouting network. However, it was

at Wolverhampton Wanderers that Frank Buckley really made his name. He joined them in 1927

and developed a marvellous youth policy. The seeds of the greatness that Wolves went on to

achieve in the 1950s, three championships, three times runners up, twice Cup winners, were

sown in Buckley's seventeen year reign. He was a strong manager, who, skillfully trading

in the transfer market, developed a homespun side at Molineux which, but for the war, might

have become as dominant as the Wolves team of the Fifties. When he arrived at Molineux, the

club were a struggling Division Two side, having lost their First Division status in 1906.

The Black Country club had been founder members of the Football League in 1888, and won the

Cup in 1893 and 1908, but those glorious days were long gone. They missed relegation to

Division Three by just three points in both 1928 and 1929, but by 1932 the Buckley magic was

working as the club won the Second Division championship, finishing a couple of points above

runners up Leeds. In Buckley's early years at Wolves, he signed some outstanding players,

including Bryn Jones and he also brought through future England half backs and captains Stan

Cullis and Billy Wright. Although the Wolves team struggled initially, avoiding relegation

the first year by just a couple of points. Gradually, Buckley managed to rebuild the club to

such an extent that they were runners up in the League in both 1938 and 1939 and were one of

the most feared sides in the country. After pipping Wolves for the title in the previous

season, at the start of the 1938-39 season, the Gunners were seeking a replacement for

schemer Alex James, who had recently retired. They broke the British transfer record by

paying Buckley £14,000 to buy his Welsh inside forward Bryn Jones. Jones had been discoverd

in Welsh Non-League football with Aberavon, costing nothing. The deal brought Buckley's

total sales of players in four seasons to £110,000. Buckley's chief contribution to the

subsequent Wolves success lay in his selection of Stan Cullis as captain of the club.

Cullis, a natural leader of the old school, already believed in hierarchy and discipline, a

faith further developed by his wartime service in the Army. When Stan Cullis retired

following Wolves missing out on the championship again at the end of 1946-47 he was the

obvious choice to become the next manager at Molineux. Cullis continued the regime

introduced by Buckley, hard work in training, strict discipline at the club and all out

attack on the field. After 17 years at Molineux, Buckley decided to end what had been

described as a contract for life in February 1944. He moved on to Third Division Notts

County, where he was paid £4,000 a year. He didn't achieve much in his couple of years at

County and within hours of his resignation in January 1946, he took charge at Hull City,

another Third Division side. As ever, Buckley continued to have a flair for publicity and

in March 1948 he persuaded First Division Derby County to sell Raich Carter for a nominal

fee. As well as playing, Carter would also be Buckley's Assistant Manager. It was only a

temporary partnership and when Buckley resigned within weeks, Carter was given complete

charge and Hull's attendances boomed. Willis Edwards had been demoted by Leeds after a

disasterous year in which Leeds United had flirted with relegation to the Third Division in

the 1947-48 season after ignominiously being relegated from Division One in the previous

year. Realising their mistake in appointing Edwards, the Leeds board went for a big name to

replace him and selected the sixty-four year old Buckley, who promptly resigned from Hull.

Leeds had often struggled financially and the business acumen of Buckley was another

attraction for them. In his time at Molineux he had generated a £100,000 profit one year and

he was good at discovering and selling young talent, something he would have the opportunity

to practice at Elland Road. Leeds fans remember Buckley for discovering John Charles, who

signed for the club on his seventeenth birthday on 27th December 1948, and went on to become

one of the biggest British stars of the 1950s. Buckley cleared out all the club's older

players and raised the admission prices at Elland Road. In his first season, Leeds finished

fifteenth. He had stopped the decline, with the team also showing promising signs. Tommy

Burden, recommended by Willis Edwards, was signed from Chester. Buckley had known him since

he was a teenager from his days at Wolves. He became captain and was very popular. Burden

had the player's respect. Buckley brought innovation and eccentricity to Leeds. He

introduced dance training to improve the players' agility and balance, with the PA blaring

out music on the Elland Road PA system, and a number of odd mechanical devices, all designed

to improve the players' skill with the ball. He organised and refereed practice matches for

the younger players. Buckley had an abrasive side to his character and soon fell out with

inside forward Ken Chisholm, an assertive Scot who had served in the RAF as a fighter pilot

and scored seventeen goals in forty League matches for Leeds. So Chisholm went to Leicester

City in an exchange deal that brought Ray Iggleden to Elland Road. As at Molineux, Buckley

developed a strong youth policy and built impressive sides, despite continuing financial

difficulties. He never got Leeds the promotion they craved, but established an attractive

side, spearheaded by Charles, which was usually in the top five or six and made it through

to the Cup sixth round for the first time in the club's history in 1950. He also traded

effectively in the transfer market, buying cheap and selling big, as he had at Molineux. He

bought Roly Depear a centre half from Boston for £500 in May 1948, and just over a year

later had sold him to Newport for a £7,500 profit. Two of his biggest sales were

internationals Con Martin and Aubrey Powell, each of whom attracted five figure fees. That

was typical of the man and Leeds United's financial position strengthened noticeably under

Buckley. Despite the importance of Charles to his side, Buckley's business acumen always

shone through. Charles would have fetched Leeds a small fortune. But, as yet,

he was not keen to go, and the directors had no desire to sell him. Despite all the

idiosyncrasies and flamboyance, Buckley knew exactly what he was doing and built a strong,

if erratic, side around John Charles, which came close to promotion a couple of times. He

had started with Leeds in a very precarious position and improved from eighteenth in

Division two the season before his arrival, to stabilize the club and achieve a fifteenth

spot in his first season of 1948/49. The real improvement came as his new charges started to

gel with a fifth place and an FA Cup run to the Quarter Finals in 1949/50. This was followed

by a fifth in 1950-51 and a sixth in 1951-52 but with everyone expecting promotion, the club

slumped to a disappointing tenth place finish. After five years at Elland Road, and then

aged seventy, Buckley decided he could take them no further with the limited funds available

and resigned in April 1953. He moved on to manage Midlands club Walsall, another Third

Division outfit, but left in September 1955 at seventy-two years old, perhaps realising that

his authoritarian approach was out of touch with the post war game. He died in Walsall, aged

eighty-two, on 22nd December 1964.

| Competition | Played | Won | Drawn | Lost | For | Against |

| League | 210 | 81 | 60 | 69 | 302 | 283 |

| F.A. Cup | 14 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 22 | 23 |

| Total | 224 | 87 | 63 | 74 | 324 | 306 |

| |

Tributes and Obituaries

Spartacus Educational: John Simkin: September 1997 (updated August 2014).

Frank Buckley

Franklin (Frank) Buckley was born in Urmston, near Manchester, on 3rd October, 1882. His father, John Buckley, was a sergeant in the British Army and was responsible for the military training of the local yeomanry and territorial units.

Buckley won a scholarship to St Francis Xavier's College for Boys in Liverpool. He enjoyed the sports and physical activities that were an integral part of the Jesuit philosophy of Muscular Christianity an idea developed by Charles Kingsley

and Thomas Hughes.

In 1898 Buckley left school and began work as an office clerk. He was also a member of the 1st Volunteer Battalion of the Manchester Regiment. On 24th February 1900 he signed-up for a 12 year engagement with the 2nd Battalion of the

King's Liverpool Regiment. He expected to be sent to South Africa to fight in the Boer War but instead was despatched to Ireland.

In September 1900 he was promoted to the rank of Corporal. By 1902 he was a Lance-Sergeant and the following year he gained the rank of Gymnastics Instructor (First Class). While in Ireland he represented the regiment at football,

cricket and rugby.

A talented footballer, he played for King's Liverpool Regiment against the Lancashire Fusiliers in the final of the Irish Cup. He was "spotted" by a scout from Aston Villa who suggested he go to England for a trial. He did this and George

Ramsay persuaded him to join the club. On 30th April 1903, Buckley paid a fee of £18 to buy himself out of the army.

Buckley joined a team that included Jimmy Crabtree, Alex Leake, Howard Spencer, John Devey, George Wheldon, Stephen Smith, George Johnson, Bobby Templeton and Charlie Athersmith. Buckley failed to make the first team and the

following year, along with his brother, Christopher Buckley, moved to Brighton & Hove Albion in the Southern League.

In 1906 Buckley joined Manchester United. He made his debut against Derby County on 29th September 1906. He joined a team that included Charlie Roberts, John Picken, John Peddie, Sandy Turnbull, George Wall, Jimmy Turnbull, Billy

Meredith, Charlie Sagar, Dick Duckworth and Alec Bell.

A centre-half, Buckley served as understudy to Charlie Roberts, who at the time was playing for England in this position. He spent most of the time in the reserves. In April 1907 Thomas Blackstock collapsed after heading a ball during a

reserve game against St. Helens Town. Buckley, who was standing nearby, helped to carry Bradstock, who was only 25 years old to the changing-room. Blackstock died soon afterwards. An inquest into his death returned a verdict of

"Natural Causes" but Buckley believed he had died of a heart-attack or seizure.

After only playing three games for Manchester United Buckley decided to move to neighbours Manchester City. He played in 11 games in the 1907-08 season before joining Birmingham City. Buckley earned himself a regular place in

Birmingham's first-team and scored 4 goals in 55 games during the next two seasons.

In May 1911 Buckley joined Derby County in the Second Division. Buckley and the team's top goalscorer, Steve Bloomer, played an important role in Derby winning the league title and promotion to the First Division of the Football League

in the 1911-12 season. Buckley was described by one football journalist as being "tall, heavily built, pivotal, hard-working and forceful when attacking."

Buckley won his first international cap for England against Ireland on 14th February, 1914. The English team that day included Bob Crompton, Sam Hardy, Edwin Latheron, Jesse Pennington and Danny Shea. England lost the game 3-0 and

Buckley was dropped from the team.

After scoring 3 goals in 92 games for Derby County Buckley moved to Bradford City in May 1914. Buckley only played in four games for his new club before the outbreak of the First World War. In October 1914, the Secretary of State,

Lord Kitchener, issued a call for volunteers to both replace those killed in the early battles of the war.

On 12th December William Joynson Hicks established the 17th Service (Football) Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment. This became known as the Football Battalion. According to Frederick Wall, the secretary of the Football Association,

Buckley was the first person to join the Football Battalion. The first commanding officer was Henry Fenwick, a career soldier. As Buckley had previous experience in the British Army he was given the rank of Lieutenant. He eventually was

promoted to the rank of Major.

Within a few weeks the 17th Battalion had its full complement of 600 men. However, few of these men were footballers. Most of the recruits were local men who wanted to be in the same battalion as their football heroes. For example, a

large number who joined were supporters of Chelsea and Queen's Park Rangers who wanted to serve with Vivian Woodward and Evelyn Lintott.

The Football Association eventually called for all professional footballers who were not married, to join the armed forces. Some newspapers suggested that those who did not join up were "contributing to a German victory." The Athletic

News responded angrily: "The whole agitation is nothing less than an attempt by the ruling classes to stop the recreation on one day in the week of the masses ... What do they care for the poor man's sport? The poor are giving their lives

for this country in thousands. In many cases they have nothing else... These should, according to a small clique of virulent snobs, be deprived of the one distraction that they have had for over thirty years."

By March 1915, it was reported that 122 professional footballers had joined the battalion. This included the whole of the Clapton Orient (later renamed Leyton Orient) first team. Three of them were later killed on the Western Front. At the

end of the year Walter Tull who had played for Tottenham Hotspur, Northampton Town and Glasgow Rangers joined the battalion. Buckley soon recognised Tull's leadership qualities and he was quickly promoted to the rank of sergeant.

On 15th January 1916, the Football Battalion reached the front-line. During a two-week period in the trenches four members of the Football Battalion were killed and 33 were wounded. This included Vivian Woodward who was hit in the

leg with a hand grenade. The injury to his right thigh was so serious that he was sent back to England to recover.

Major Buckley's batman, Thomas Brewer, who had played football for Queen's Park Rangers, was killed by a German sniper. Buckley was so upset by Brewer's death that he offered to pay for the education of his three children.

The Football Battalion had taken heavy casualties during the Somme offensive in July. This included the death of England international footballer, Evelyn Lintott. Major Buckley was also seriously injured during this offensive when metal

shrapnel had hit him in the chest and had punctured his lungs. George Pyke, who played for Newcastle United, later wrote: "A stretcher party was passing the trench at the time. They asked if we had a passenger to go back. They took

Major Buckley but he seemed so badly hit, you would not think he would last out as far as the Casulalty Clearing Station."

Buckley was sent to a military hospital in Kent and after operating on him, surgeons were able to remove the shrapnel from his body. However, his lungs were badly damaged and was never able to play football again.

In January 1917 Buckley was back on the Western Front. The Football Battalion attacked German positions at Argenvillers. Buckley was "mentioned in dispatches" as a result of the bravery he showed during the hand-to-hand fighting

that took place during the offensive. The Germans used poison gas during this battle and Buckley's already damaged lungs were unable to cope and he was sent back home to recuperate.

In 1919 Frederick Wall, the secretary of the Football Association, suggested that Buckley should become manager of Norwich City in the Southern League. Buckley developed the reputation for finding talented young players. According

to Patrick A. Quirke, the author of The Major: The Life and Times of Frank Buckley (2006): "Buckley relied on tips and advice from his old Army comrades who lived in various areas around Britain. This country-wide scouting network,

which he was to call upon time and again during his long managerial career, was the envy of many, as his scouts were all former players and knew what to look for in a young footballer."

While at Norwich City Buckley discovered Samuel Jennings, a miner, playing for Basford United. However, the club was in serious financial difficulties and Buckley was forced to sell Jennings to Middlesbrough for £2,500. In March 1920

a Football League made an illegal approach for one of Buckley's young players. When the directors refused to make a complaint to the Football Association, Buckley left the club.

For the next three years Buckley worked as a commercial traveller for Maskell's, a confectionary manufacturer based in London. The job involved travelling all over England. While travelling on a train in 1923 he met Albert Hargreaves, a

director of Blackpool football club. He arranged a meeting with Blackpool's president, Linsay Parkinson, and as a result he was appointed manager of the club. At that time Blackpool was in the Second Division of the Football League.

Buckley's first decision was to abandon Blackpool's traditional strip and brought in players' shirts of bright orange, or tangerine as it became known. Buckley wanted the club to be seen as "bright and vibrant" and a representative of the

"new age".

In his first season Blackpool finished 4th. The club's star player was Harry Bedford, who was the country's top goalscorer with 34 goals. After scoring 112 goals in 169 games for Blackpool, Bedford was transferred to Derby County for

£3,000 in 1925.

Buckley signed William Tremelling from Retford Town as a replacement for Harry Bedford. He made his Football League debut against Manchester United in March 1925. Unfortunately, he broke his leg the following season and did not

return to the team until the 1926-27 season. Tremelling ended up as the club's leading scorer with 30 goals in 26 games.

Buckley believed strongly in the importance of physical fitness. He imposed strick orders as to what the players could eat and drink. They were instructed to have early nights two days prior to a fixture and not to socialise during this time.

Buckley introduced physiotherapy and gained a reputation for getting injured players back to fitness in a short time.

In May 1927 Buckley moved to Wolverhampton Wanderers. As Patrick A. Quirke, the author of The Major: The Life and Times of Frank Buckley pointed out: "His experience at both Blackpool and Norwich of acquiring skilled and talented

players at little or no cost and then selling them on at a healthy profit was extremely appealing to those concerned with club finances."

As at Blackpool he introduced a new football strip. He designed the shirts himself. They were deep gold with black trimmings. He also brought in new training methods he had used at Blackpool. This included exercises with Indian clubs

and weight training.

Buckley gave each of his players a small pocket book in which was printed details of the conduct he expected from them. As well as advice on not smoking, he insisted that they did not go out socialising for a least two days prior to a

match. Buckley also informed the Wolverhampton public of these regulations and asked them to contact him if they saw a player breaking the rules.

Over the years Buckley built up a network of football scouts who attempted to discover talented young players. In 1927 he purchased Dai Richards from Merthyr Town. This was followed by Reg Hollingsworth, a centre-half from Sutton

Junction, Billy Barraclough from Hull City, Billy Hartill a centre-forward who was playing for the Royal Horse Artillery and Charlie Phillips from Ebbw Vale.

Noel George, the club goalkeeper, was diagnosed as being terminally ill with a disease of the gums and died in 1929. He had played in 292 games for Wolves. Buckley was convinced that George's death was due to ill-fitting dentures.

From that time on he made sure that all his players who wore dentures were examined by a dentist every six months.

Wolves lost to lowly Mansfield Town 1-0 in the FA Cup in 1929. Buckley was so upset with the performance of his players that he organized a training-run through Wolverhampton town centre for the first-team players on a market-day

during the following week.

In the 1929-30 season Billy Hartill scored 33 goals in 36 games. This included all five against Notts County at Molineaux. Despite these goals Wolves could only finish in 9th place in the league.

The following season Wolves finished 4th in the Second Division. Billy Hartill was again top scorer with 30 goals in 39 appearances. Buckley added Tom Smalley for his first-team squad in 1931. He was a coalminer who had been playing

his football for South Kirkby Colliery. Smalley was to develop into an important member of the team.

Billy Hartill scored 30 goals with hat-tricks against Plymouth Argyle, Bristol City, Southampton and Oldham Athletic, in the 1931-32 season and helped the club win the Second Division championship. Charlie Phillips was also in great form

adding 18. The club scored 118 goals that season.

The championship winning team that season included only one player that had not been signed by Buckley. The Wolverhampton Express and Star report on the success included the following tribute: "By his splendid work with the Wolves

he has built up a reputation as a football manager second to none in the country... At the Molineux Ground he has proved himself a splendid judge of a player. His ability to find a young talent is unequalled and despite the handicaps with

which he is faced when joining the club he has discovered a whole team, which has taken Wolves into the highest flight."

In August, 1933, Buckley purchased Bryn Jones from Aberaman for a fee of £1,500. In his first season at Wolves he scored 10 goals in 27 appearances. Although very popular with the fans, Jones was unable to immediately turn Wolves

into a successful side. Billy Hartill remained in good form scoring 33 goals. This included four against Huddersfield Town and hat-tricks against Blackburn Rovers and Derby County. In the 1933-34 season they finished in 15th place in the

First Division. However, crowd attendances had doubled and the board declared profits of £7,610.

Stan Cullis joined Wolves in 1934. Cullis later recalled: "Major Buckley, apparently, decided very quickly that I might make a captain." When Cullis was only 18 years old and in the "A" team he was told by Buckley: "Cullis, if you listen and

do as you are told, I will make you captain of Wolves one day."

1934 also saw the arrival of Jimmy Utterson, a goalkeeper from Glenavon in the Irish League. Unfortunately, he only played in 12 games before he died from head injuries he had received in a game against Middlesbrough.

Major Buckley continued to search for new talent and in 1934 he signed Billy Wrigglesworth, a winger from Chesterfield, David Martin from Belfast Celtic and Tom Galley, a midfielder, from Notts County. In the 1934-35 season Wolves

finished in 17th place in the First Division winning only 15 of their 42 games. Billy Hartill was again top scorer with 33 goals.

In 1935 Buckley signed Alex Scott, a goalkeeper, for a fee of £1,250 from Burnley. However, he upset the Wolves' fans by selling Billy Hartill to Everton. A few months later he sold Charlie Phillips to Aston Villa for £9,000. It seemed that

Buckley and the Wolves board were more concerned with making a profit than winning the First Division championship. Wolves again struggled in the 1935-36 season finishing in 15th place, only five points above the relegated teams,

Aston Villa and Blackburn Rovers.

Wolves started the 1936-37 season badly. They won only four games out of their first 14 and after a 2-1 defeat at home to Chelsea the crowd invaded the pitch from the South Bank and called for the resignation of Major Buckley. The

crowd uprooted the goalposts before police reinforcements restored order. Buckley was offered police protection but he refused and walked home alone. Newspaper reports suggest that over 2,000 people were involved in the

demonstration against Buckley.

Buckley later recalled that the main cause of this hostility was his policy of selling established players in order to balance the books. However, he argued this enabled him to play, younger, more talented players who became known as

the "Buckley Babes".

In January 1937, Buckley again upset the Wolves' fans by selling Billy Wrigglesworth to Manchester United, who had the very good record for a winger, scoring 21 goals in 50 games for the club. However, Wolves had a good run in the

league after Christmas and eventually finished in 5th place behind champions Manchester City.

In the summer of 1937 Buckley was approached by a chemist called Menzies Sharp. He claimed he had a "secret remedy that would give the players confidence". It is believed that Sharp's ideas were based on the experiments of

Serge Voronoff, a French doctor, who had been born in Russia. Between 1917 and 1926, Voronoff carried out over five hundred transplantations on sheep and goats, and also on a bull, grafting testicles from younger animals to older

ones. Voronoff's observations indicated that the transplantations caused the older animals to regain the vigor of younger animals.

Sharp's "gland treatment" involved a course of twelve injections. Buckley later explained: "To be honest, I was rather sceptical about this treatment and thought it best to try it out on myself first. The treatment lasted three or four months.

Long before it was over I felt so much benefit that I asked the players if they would be willing to undergo it and that is how the gland treatment became general at Molineux."

Two Wolves players, Dicky Dorsett and Don Bilton, refused to undergo the "gland treatment". According to Patrick A. Quirke, the author of The Major: The Life and Times of Frank Buckley (2007): "Dorsett, a well-established and

experienced footballer, had stood up to Major Buckley's insistence (some might say bullying) on a number of occasions."

Don Bilton recalls that he was signed by Major Buckley from York City. On his arrival at the club he was instructed by Buckley to report to the medical room for gland injections. Bilton replied: "I'm sorry Sir, but I am only seventeen and

still under my father's guidance. He will not want me to have injections." Buckley told him that he was under contract and had to do as he was told. Bilton's father went to see Buckley the following day and after a heated row the manager

backed-down. However, Bilton claimed that: "Buckley was not at all pleased by this and I never did much good at Wolves after that!"

Rumours circulated that Wolves players were being injected with "gland extracts from animals". Tommy Lawton, who was a member of the Everton team that lost 7-0 to Wolves, believed that these injections were improving the

performance of the players. He claimed that before the game he tried to speak to Stan Cullis but "he walked past me with glazed eyes".

On 9th April, 1938, Dicky Dorsett and Dennis Westcott both scored four goals when Wolves beat Leicester City 10-1. After this defeat the club complained to Montague Lyons, the Leicester member of the House of Commons that the

Wolves players were being injected with monkey glands. Lyons demanded that the government instigate an investigation into this treatment. When Walter Elliot, the Minister of Health, rejected this request, Emanuel Shinwell, the Labour

MP, suggested that considering Wolves' impressive form, ministers of the Conservative government should be put on a course of these injections.

The Football League carried out an investigation into the "monkey gland" treatment. However, it refused to ban these injections but they did arrange for a circular to be posted in the dressing rooms of every club in England and Wales.

This declared that players could take monkey glands but only on a voluntary basis.

At the beginning of the next season Buckley appointed Stan Cullis as captain of Wolves. In his autobiography, All for the Wolves (1960), Cullis claimed: "Buckley spent many hours drilling me in the precious art of captaincy, telling me

in no ambiguous terms that I was to be the boss on the field. No youngster of eighteen could ask for a better instructor than the major, who laid the foundations of the modern Wolves during his sixteen years at Molineux".

Patrick A. Quirke, the author of The Major: The Life and Times of Frank Buckley argues that Buckley developed a unique style of management: "At whichever club he was at, to his players Major Buckley was not only their manager;

he was their coach and trainer.... Buckley used training methods that might now be seen as crude forms of psychological behaviour modification."

For example, Gordon Clayton, the Wolves centre-forward, went through a barren period when he was unable to score. He got barracked by the Molineux crowd so badly that he considered giving up the game. Buckley considered

him a "grand centre-forward" and argued that it would be a "football tragedy" if this happened. Buckley's wife suggested that Clayton should have a "course of psychology" with a local doctor. This was a great success and Clayton

went on to score 14 goals in the next 15 matches.

After finishing the course of treatment Gordon Clayton wrote to Dorothy Buckley: "I just learnt that it was you who was actually responsible for my treatment. I am very pleased with my success so far and I know you will be equally

pleased. I cannot really thank you enough for what you have done... As you no doubt know the very name of Wolverhampton Wanderers was a nightmare to me. I detested the place. I do not think I was liked or respected by a single

person with the exception of Major Buckley, who I have no doubt was always interested in my welfare, even though I must have exasperated him often."

Major Buckley did not like the idea of football players being married. He thought that wives might "get in the way" of players concentrating on developing their skills. He also thought that a wife's anxiety about her husband's safety

might affect him and his performance. Buckley had forty players in his 1937 squad and all were bachelors.

Buckley developed a more direct style of playing football. "It was simply the task of the defenders to get the ball forward as quickly as possible and not to over-elaborate their roles. The wingers were to take opposition defenders

on and cross the ball to the central attackers whose job it was to put the ball in the net... He wanted fewer dribbling moves and more passing." Stan Cullis said that players were expected to do exactly as Major Buckley ordered

otherwise "you'd very soon be on your bicycle to another club."

In the 1930s football teams travelled to away grounds on the day of the match. Buckley observed that players often arrived tired and fatigued. He therefore arranged for players to stay overnight in hotels when playing distant away

fixtures. Buckley even argued "that where possible players should be ferried to games by air" and predicted that in future every top club would have its own helicopter to do this.

It was claimed that sometimes Buckley resorted to underhand tricks. John Jones of Everton recalls going to Molineaux and finding the ground "a sea of mud" even though there had been no rain for sometime. Jones complained

that "we were on our bottoms more than our feet" during the game whereas Wolves had no trouble in this regard as they were all wearing long studs. Everton complained to the Football Association about what had happened and

soon afterwards the FA banned the over-watering of pitches.

Buckley wanted to take his team on a tour of Europe before the start of the 1937-38 season. However, the Football Association refused permission for this to go-ahead due to "the numerous reports of misconduct by players of the

Wolverhampton Wanderers Club during the past two seasons." There had been seven sendings-off while Buckley was manager of the club. However, as Buckley pointed out, four of these were accounted for by two players, Charlie

Phillips and Alex Scott.

Stan Cullis and his teammates wrote to the FA claiming: "We would like to state that far from advocating the rough play we are accused of, Major Buckley is constantly reminding us of the importance of playing good, clean and

honest football, and we as a team consider you have been most unjust in administering this caution to our manager."

Major Buckley was gradually building up a very good squad that included Stan Cullis, Gordon Clayton, Bill Morris, Dennis Westcott, George Ashall, Alex Scott, Jack Taylor, Tom Galley, Dicky Dorsett, Bill Parker, Bryn Jones,

Joe Gardiner and Teddy Maguire.

Buckley sold Gordon Clayton to Aston Villa in October 1937. Dennis Westcott replaced Clayton as centre-forward and scored his first hat-trick against Swansea City. In the 1937-38 season Wolves finished second to the mighty

Arsenal in the First Division. Westcott finished the season as top scorer with 22 goals in 28 appearances.

At the time, Arsenal dominated the First Division championship, having won it four times in six years. Alex James, their creative inside-forward, had recently retired. The club was looking for a replacement and Buckley decided to

sell his star player, Bryn Jones for the world record fee of £14,000 (£6.9 million in today's money). Politicians were outraged by the money spent on Jones and the subject was debated in the House of Commons. Buckley later

recalled that people would spit at him and his wife as they walked around Wolverhampton after he sold Jones.

As Stan Cullis pointed out: "Throughout the middle years of the 1930s, Major Buckley steadily built up the team he believed would capture most of the honours in England. From the large numbers of lads he brought to Molineux for

trials, he signed enough professionals both to form his team and to bring in a fortune from the transfer market. At a time when a five-figure transfer fee still astounded the football public, Major Buckley earned £130,000 for Wolves

in five years before the 1939-45 war. This spell established Wolves as one of the wealthiest football clubs in Britain."

In 1938 Major Buckley agreed a new ten-year contract with Wolves. He told the local newspaper: "Since coming to Wolverhampton ten years ago I have become so bitten by the Wanderers bug that no other club could ever interest

me. It has been a pleasure to work in the town and, while we have had our differences, they have been plainly stated. I shall be happy to spend my football life with the club I so love."

In the 1938-39 season Wolves finished second to Everton. The centre-forward Dennis Westcott scored 43 goals in 43 appearances. His fellow striker, Dicky Dorsett managed 26 goals that season. The captain of the side, Stan

Cullis, was generally acknowledged as the best centre-half in the Football League. That season also saw the arrival of teenagers, Billy Wright, Joe Rooney and Jimmy Mullen, in the side.

Wolves also enjoyed a good run in the FA Cup and beat Leicester City (5-1), Liverpool (4-1), Everton (2-0), Grimsby Town (5-0) to reach the final against Portsmouth at Wembley. Wolves lost the final 4-1 with Dicky Dorsett scoring

their only goal. Major Buckley's Wolves became the first team in the history of English football to be runners-up in the sport's two major competitions in the same year. Afterwards, it was discovered that the Portsmouth players, like

those of Wolves, had also been injected with monkey glands.

The outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 brought an end to the Football League. Buckley attempted to re-join the British Army but at the age of 56 he was considered too old. However, he did encourage all his players to join

and according to the Football Association publication, Victory Was The Goal (1945), between 3 September 1939 and the end of the war, 91 men joined the armed forces from the club.

In 1940 Buckley took command of a Home Guard unit in Wolverhampton. Buckley held nightly meetings at the local Territorial Army Hall that was situated near his home at St Jude's Court. According to Patrick A. Quirke, the author

of The Major: The Life and Times of Frank Buckley: "Being totally dedicated to individual physical fitness, Major Buckley would often march his men to the Molineux where they would use the club's exercising facilities and the pitch

itself as a training ground."

The government imposed a fifty mile travelling limit on all football teams and the Football League divided all the clubs into seven regional areas where games could take place. Wolves joined the Midland League with West Bromwich

Albion, Birmingham City, Coventry City, Luton Town, Northampton Town, Leicester City and Walsall. Wolves won the 1939-40 championship. Top scorers were Dennis Westcott (26), Dicky Dorsett (16) Jimmy Mullen (7) and Billy Wright (5).

Wolves also won the Football League War Cup in 1942 beating Sunderland 4-1. The team included Eric Robinson who was to be tragically killed during a military training exercise soon afterwards. Joe Rooney was killed in action in

1943. Bill Shorthouse was badly wounded during the D-Day landings but survived to play for Wolverhampton Wanderers after the war.

Buckley retained his belief in youth and in September 1942 he gave a debut to Cameron Buchanan. At the age of fourteen years and fifty-seven days he was probably the youngest teenager to play for a Football League club. He played

in a further 11 games before joining Bournemouth before the end of the war. Buckley also played Emilo Aldecoa, a political refugee who had been forced out of his own country by the Spanish Civil War.

Buckley resigned as manager of Wolves on 8th February 1944. This shocked the directors as they had given him a ten-year contract in 1938. During his 18 years at the helm, Buckley made £100,000 for Wolves in transfer dealings.

The following month he joined Notts County in the Third Division on the extraordinary wage of £4,500 a year. While at his new club he signed Jesse Pye. He later sold him for £10,000 to Ted Vizard, the new manager of Wolves.

In May 1946 Buckley moved to Hull City, another Third Division side. The club finished in 5th place in the 1947-48 season. In May 1948 Buckley joined Leeds United. In his first season he signed John Charles, who was later to become

a football superstar. Buckley later commented: "I shall never forget that morning when I first met John Charles. I was sitting in my office when they bought in a giant of a boy. He told me he was fifteen. He stood 6ft and weighed more than 11st."

Buckley was unable to get Leeds United promoted to the First Division and in April 1953 he moved to Walsall. Buckley was now aged seventy. Although he still had plenty of energy, "his scouting network, so long the mainstay of his talent

spotting, was breaking up as his scouts became old and retired." The club finished bottom of the Third Division in the 1953-54 season and Buckley retired the following year.

Frank Buckley died of heart-failure at his home in Mellish Road, Walsall on 22nd December 1964. The funeral took place in Wolverhampton and his ashes were scattered on the Malvern Hills.

A Half Time Report: July 6, 2015

Major Frank Buckley: From the Somme to a Cup Final

Major Frank Buckley is truly one of the game’s most fascinating figures. Born to a sergeant in the British Army, Buckley followed in his father’s footsteps, signing up to the army in 1900, where he quickly advanced through the ranks. A keen sportsman,

Buckley bought himself out of the army in 1903 and joined Aston Villa. As he approached the end of a very respectable playing career, he was called into action on the dawn of the First World War, where he became Major of the famous ‘Football

Battalion’. As a manager, Buckley was known as an eccentric and disciplinarian, his greatest achievements coming with Wolverhampton Wanderers. He introduced many new training methods and styles of man-management, which would influence

the likes of Stan Cullis, Matt Busby, Bill Shankly and arguably those of Brian Clough and Alex Ferguson. He also supposedly injected his players with small slices of monkey testicles, but more on that later.

Buckley was born on November 9th 1883 to Sergeant John Buckley, in Urmston, Manchester. He attended the Roman Catholic St Francis Xavier’s College for boys in Liverpool, where he gained a scholarship. The heavily religious secondary school

has proved something of a breeding ground for footballers, with the likes of Dixie Dean, Sammy Lee, Mike Newell and Jon Flanagan among the school’s former pupil’s. Buckley enjoyed the numerous sports on offer as a child, excelling in many, but

never thought of them as serious career paths, and he became an office clerk in 1898, standing as a volunteer of the Manchester Regiment. In 1900, at the age of 17, Buckley signed up to a 12-year agreement to fight in the Boer War.

He was never sent to South Africa though, and instead headed to Ireland, where he served for three years moving up the ranks from Corporal to Lance-Sergeant. An avid sportsman, Buckley played cricket, rugby and football whilst in Ireland, and was

discovered by an Aston Villa scout playing the latter, who recommended that he returned to England for trials in Birmingham. Buckley took his advice, paying a fee of £18 to buy himself out of the armed forces, and was successful in his trials, joining

Villa in 1903. English champions in 1900 and FA Cup winners in 1905, Buckley had joined a highly-successful club and the 20-year-old failed to break into a strong first team.

Buckley subsequently moved to Brighton, where he struggled once more, before short-term spells at Manchester United and Manchester City. Whilst at Manchester United Buckley was involved in a shocking incident when he had to carry Thomas

Blackstock off the pitch and into the changing rooms. Blackstock had collapsed after heading the ball and tragically died soon after. An inquest claimed Blackstock had died via natural causes, but Buckley was insistent that the young defender had

suffered a heart-attack or seizure. By 1907, Buckley had played for some of the country’s top teams but was 24-years-old and had only played a handful of games. He needed stability and first-team football, so he moved to Birmingham City, where he

spent two years and played much more football.

A no-nonsense defender, Buckley was a tall, solid and well-built player who led from the back throughout his career. In 1911, he joined Derby County. It was with Derby that Buckley would play his best football and earn his first and only cap for England.

He played 92 times for the Rams, earning promotion to the First Division in his first season and remaining a stalwart of Jimmy Methven’s team. Buckley’s England call-up came in 1914, aged 30, making him still one of England’s older debutant’s. A

strong England side was roundly beaten 3-0 in a shock defeat to Ireland, and Buckley never wore the white of England again. Buckley played almost a century of games for Derby when, in May 1914, he joined Bradford City; but after just four games for

Bradford, war broke out.

There was a general consensus within football that continuing as normal throughout the war would be the best plan of action, in order to keep public spirits up during a difficult time. However, it soon became apparent that the British public did not agree.

Many complained about footballers lack of involvement and by the end of 1914 the pressure had become too great. Controversial Home Secretary William Johnson-Hicks founded the 17th Service Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment, better known as

the ‘Football Battalion’, on December 12th 1914, and Frank Buckley was the first to sign up. Despite 1,800 footballers being eligible for the regiment, after 14 months there were only 122 members, which were largely down to the entire Clapton Orient

and Hearts teams signing up.

The low numbers were not a sign of cowardice among footballers, but rather that many footballers had simply joined other regiments, and the numbers for the battalion would soon grow as the war went on. The Football Battalion are well-known for their

admirable service in a number of difficult battles, suffering many heavy losses. Particular examples include the Battle of Arras, the Battle of Delville Wood and the Battle of Guillemont at the Somme. The Battalion included the great Walter Tull, who was

the first mixed raced outfield player in the Football League. Tull was noted for his gallantry and coolness, and was killed in 1918 during the Spring Offensive. There were calls for him to receive a Military Cross but they never materialised. Meanwhile

Lyndon Soe of Cardiff City was honoured with the Distinguished Conduct Medal.

It was Buckley though who was the most highly ranked of the battalion, becoming a Major during the war, and he remained known as Major Frank Buckley having survived the war once peacetime football resumed. Aged 36, and having suffered gas

attacks, there was little point of Buckley trying to revive his playing career and he instead turned to management, where he could utilise his excellent leadership qualities. Buckley took the helm at debt-riddled Norwich City in 1919, where he grew a

reputation for recruiting talented young players through the contacts he had made across the country during the war. His time at Norwich was short-lived though, and after disagreements and financial disputes with the board he left in 1920.

Failure at Norwich seemed to signal the end for Buckley in football management, and he took up a post working as a commercial traveller for Maskell’s, a confectionary manufacturer. After three years with Maskell’s, Buckley had a chance encounter

with Albert Hargreaves, a director at Blackpool. Buckley had no intentions of leaving Maskell’s, but after a meeting with president Linsay Parkinson in which Buckley was convinced he would not only be well-paid but also given funds to spend in the

transfer market, he joined the Seasiders in 1920.

Buckley’s first move as manager was to change Blackpool’s playing colours, which had been mainly red, to a very bright orange which is still worn by the club today. The idea behind the change was to display a type of vibrancy, freshness and newness

to Blackpool which Buckley hoped to bring to the Second Division side. Buckley immediately introduced strict and regimented fitness regimes, and even introduced rules regarding what players could eat and drink, well over half a century before such

rules became commonplace. Buckley is, as far as we know, the first manager in British football to have done so.

During his time at the helm, Blackpool were regarded as the fittest team in the country, and their physical conditioning was far better than most Second Division sides. Buckley brought through two of the most clinical strikers in England in the forms of

Harry Bedford and William Tremelling but lost the pair of them to bigger teams in Derby County and Preston North End. Buckley brought physiotherapists in to Blackpool before any other club had them and the Seasiders soon gained a reputation for

returning injured players to first team football sooner than other sides were able to.

After over four years at Blackpool, the Major moved to Wolverhampton Wanderers. By this point Buckley had a reputation for buying players for a pittance and selling them on for a fortune, which made him an attractive option for all financially savvy

directors in the Football League. He continued his impressive recruitment at Wolves, where he had one of the most extensive scouting systems in the country. Whilst most teams would look to the local schoolboy systems for future players, Buckley

wanted to recruit on a national scale, and was just as happy to poach players from Plymouth or Carlisle, as he was those based in Wolverhampton.

It was at Wolves that Buckley really became known as one of the game’s great eccentrics. After a humiliating cup defeat to Mansfield, he made his players train in Wolverhampton town center, drilling them with a hard physical training session with a lot

of running. It is now that we must come onto the oh-so-tricky issue of monkey testicles. It sounds like the stuff of myth and legend, and some claim it is just that. Buckley was known for liking to drum up media attention and publicity, and such a rousing

story garnered mass interest and hysteria around the club.

However, the story is not so easily dismissable. Buckley was first approach by a chemist named Menzies Sharp in 1937. Sharp had learnt from the famous French surgeon of Russian descent by the name of Serge Voronoff. He was at one time highly

respected for his theories regarding the grafting a monkey testicles, but the results Voronoff had witnessed turned out to be mere placebo effects, and he lived out his old age in ridicule. A sceptic, Buckley took the treatment for 3 months before

subjecting it to his players, but was impressed by the results. Two Wolves players, Dicky Dorsett and Don Bilton, refused the injections despite techniques described as “bullying” by Buckley.

Soon after the treatment, Wolves rawed on to some incredible results. A 7-0 thrashing of Everton was followed by a 10-1 demolition of Leicester City, although four of the ten goals scored against Leicester were by the injection-free Dicky Dorsett. After

both of these games, Everton and Leicester complained to the relevant authorities, with Everton legend Tommy Lawton claiming “he [Stan Cullis] walked past me with glazed eyes”. The claims were largely put to bed after Wolves’ FA Cup final defeat to

Portsmouth in 1939.

Wolves were hot favourites to win the cup against an industrious Portsmouth side, but were roundly beaten 4-1. The 1938/39 season would prove the closest Buckley ever came to silverware, as Wolves became the first team in England to finish as

runners-up in the two biggest competitions, the First Division and the FA Cup. Buckley had also guided Wolves to a second place finish in the previous season, when they finished an agonizing one point behind champions Arsenal. When the club were

arguably at their peak, the football season was halted due to the Second World War. After the cup final defeat the Football League ruled that the injections were not against any rules, providing they were not forced upon players.

Buckley’s time at Wolves can prove tricky to evaluate. The club made a fortune under his stewardship, although supporters often grew frustrated at the sales of star players. In the 2013 Football League 125 year celebrations, Wolves fans voted Buckley

as the club’s third greatest ever manager, but the man who topped that poll was perhaps more telling. Stan Cullis unsurprisingly scored a massive 72% of the overall vote. Cullis was brought to Wolves by Buckley, and the Major had a great impact

upon the young centre-half, eventually making him club captain and instilling him with the leadership qualities that would see Cullis guide Wolves to three league titles, one FA Cup and scalps against some of Europe’s biggest clubs.

There was to be some silverware for Buckley at Wolves. The team lifted the 1942 Football League War Cup, with a 4-1 defeat of Sunderland. After the war, Buckley joined Notts County, to the shock of the Wolves supporters and directors. Buckley had

been offered a colossal £4,500 a year contract in Nottingham, and so he swapped the First Division runners-up for the Third Division strugglers. The Major hadn’t lost his touch, signing Jesse Pye on a free transfer in 1945, he sold him for £10,000 to

former club Wolves only a year later. Buckley didn’t spend long at County though, and soon headed to East Yorkshire, and another ambitious Third Division side in the form of Hull City.

Buckley spent only two year at Boothferry Park but he did make a real contribution to the club, signing the likes of Jack Taylor and Raich Carter, the latter of whom would replace Buckley as Hull City manager, when the Major headed to Leeds United. By

now, Buckley was getting old. He was 65 when he joined Leeds, and failed to achieve his objective of getting the team into the First Division. The Major did have one last great gift to the world of football though. Buckley brought a young man of big

build by the name of John Charles to Elland Road. The Major was unsure of Charles’ best position, an issue that would divide opinion long after his retirement. As such, Buckley played Charles in a variety of positions for the reserves; and the result was

one of the most complete footballers in the history of the game.

Buckley left Leeds after 5 years of service to the club, without a promotion to his name but he had signed John Charles and Jack Charlton, who would gain promotion under Carter two years after Buckley left Leeds. The Major headed to Walsall. Now

aged 70, the majority of Buckley’s connections and scouts across the country were either dead or retired. His recruitment skills were massively depleted, and the club were relegated in his second season at the helm, Buckley knew it was the end and

retired.

Buckley remained in Walsall for another 10 years, where he died, aged 82. His ashes were scattered on the Malvern Hills. Major Frank Buckley made a great contribution to both the world of football and the war effort. He revolutionized training regimes,

dietary requirements and scouting systems. At Wolves, he inspired the greatest team the city has ever seen, even if it only came to full fruition under his pupil after Buckley had left the club. Seven of the starting XI in the victorious 1949 Wolves FA Cup

team had been signed by Buckley. In the forms of Stan Cullis, Billy Wright, Jimmy Mullen, John Charles, Jack Charlton and more, Buckley gave Britain some of it’s greatest ever players. In April 2015, Buckley was awarded the prestigious ‘Contribution

to League Football’ award by the Football League.

Major Buckley, the last of the old school :Duncan Steer: September 25, 2011: Football First published: 2004

In April 1944, a man of military bearing dressed in plus-fours went on BBC radio to talk about the future of football. Britain was at War, strikes were brewing across the country and the availability of lemons in the shops was considered headline news.

But Major Frank Buckley had a vision to cheer his audience: a glossy future of British and European football leagues, with top teams whizzing over the continent in aeroplanes and every fan seated in a covered and heated stadium. Why, even

refereeing would be better after the War, so long as officials were recruited from the ranks of former players and paid a full-time wage.

To the uninitiated, the 61-year-old Major, a veteran of the Boer War and the Somme, with his tweeds and old school accent might not have been the obvious choice to talk about the people’s game. But the Major was the highest-paid and most

controversial football manager in the country. He had turned Wolves from a struggling second division outfit into one of the best and richest teams in the land via a mix of visionary and legally questionable methods that had re-invented football

management.

The Major – always “the Major” never “Frank” or “Mr Buckley” – stood before the nation as a man with the footballing Midas touch: his own salary of £4500 a year was as much as a member of the Wartime cabinet earned and ten times as much as the

maximum wage for a footballer. Alongside news of the war and lemon shipments, Buckley’s astronomical reported earnings had, indeed, stirred some controversy in the papers.

But controversy was the Major’s meat and drink. If his outward appearance was a throwback, his ideas were ferociously modern: he injected his players with animal extracts to improve their speed and stamina; his teams were banned from playing in

Europe because their disciplinary record was so poor; he used psychologists and ballerinas and music-hall stars to help with training – and watered pitches to favour his own team. He said that a well-organised football club should have only one

director – and that said director should, preferably, be dead.

But the Major was not just a journalists’ dream, ever-ready with some new scam and an imperious quote. Over his 45-year management career, he discovered some of the biggest names in football history – from Billy Wright to John Charles to Jack

Charlton – and gave the game ideas, on and off the field, that still seem visionary today.

How he became the biggest name in football is one of the game’s most remarkable stories.

Born in Manchester in 1883, Buckley had been a journeyman centre-half before World War I: he wore the colours of Aston Villa, Manchester City, Manchester United, Birmingham, Derby and Bradford and, for one game in 1914, England. First entering

the army as a private at the start of the Boer War in 1899, he rose to the rank of Major during World War I, during which he led the Footballers’ Battalion, a unit made up entirely of ex-pro players. Injured by a grenade at the Battle of the Somme, Buckley

was twice mentioned in depatches during the War. When he returned to civilian life, he kept the title ‘Major’ and adopted a suitable sartorial style: the tweeds that would become his trademark.

After stints as manager of Norwich and then Blackpool, he came to Wolves, the club with which he would become synonymous, in 1927. Though the era of the manager’s job being the most influential at a football club was still decades away, the Major

immediately set about reforming the club in his own image. He changed the team’s strip, brought in new gym equipment, laid down a code of behavour for his staff – and began to offload any players considered too old or slow for his footballing

masterplan and replace them with young products of his own, innovative scouting system. In 1932, Wolves returned to the top flight, announced a profit and built a huge new stand at Molineux.

Buckley’s rise came in the wake of the first of the great modernising managers, Herbert Chapman, who won the League with both Huddersfield and Arsenal and had pushed for more managerial control, more developed tactics and a roster of advances

including floodlights and numbered shirts. Chapman’s premature death from pneumonia in January 1934 left Buckley to take up the baton as the most forward-thinking football manager in the country.

Forward-thinking – and no-nonsense: “I’ve spoken to players galore from different eras about the Major and the first thing they always said was – ‘Oh, he frightened me’,” says Eddie Holding who played under the Major at Walsall in the 1950s, and

observed him as a Wolves fan in the ’30s. “He was a very imposing figure: with his ramrod straight back, and brogues and plus-fours, he looked every inch a Major. The nearest manager to him in a more modern era would be Brian Clough. He ran

clubs with a rod of iron. That incident with the England players talking about going on strike in Turkey – the Major would have sacked the lot of them on the spot. He wouldn’t have waited to hear their opinion or talk to agents or lawyers: he’d have

sacked them on the spot and sent out a team of reserves. ”

Blooding young players at the expense of experienced campaigners was indeed Buckley’s speciality. As his Molineux revolution gathered pace, it was soon being suggested that he could tell if a player had Division One promise simply from the

handwriting on his application form. Among the players he brought to Wolves in the 1930s were Stan Cullis and Billy Wright: over the next 20 years both would become club (and England) legends. Neither would forget their first brush with the Major.

“He looked me up and down, as I imagine a bloodstock-owner would look at a racehorse,” recalled Cullis of his ‘interview’ in 1934. “He said, ‘Stand up’ and tapped me on the chest. He said, ‘Are you frightened?’ I said, ‘Of what?’ He said, ‘Of getting

hurt.’ I said, ‘No.’ That was all he said to me. He had some words with my father, which I couldn’t hear, and I was a professional footballer.”

Three years later, it was Billy Wright’s turn to meet the Major.

“From the moment I crossed the threshold, two things caught my attention,” he remembered. “First, the neatness of everything. Secondly, the personality of the man who sat in a swivel chair behind a magnificent oak desk. ‘Hello, sonny,’ he said. ‘My,

we’ll have to make you grow.'”

Ready to go on the stump personally to footballing backwaters to scout out new players, Buckley built his team on the cheap. Favoured sources of new players were the coal-mining areas of South Wales and the north-east of England. Wolves evolved

a scouting and youth system on an unprecedented scale that allowed Buckley to develop a young, physical and above all fast team that became known as the Buckley Babes, 20 years before Matt Busby’s Man Utd team were similarly monikered.

Buckley’s tactics revolved around breaking quickly from defence. His watchword was attack: Wolves scored over 100 goals when they were promoted to the top flight in 1932. They scored 80 goals the following year in the top flight – but conceded 96

and kept their place in the division only after coming from behind to beat Everton on the last day of the season.

The Major was not big on team talks and intricate tactics. “He believed in the basics,” recalls Eddie Holding. “Before one game at Walsall, he brought in one of those boards, with the players represented by magnetic markers and he put them all in

position and said: ‘When the whistle blows, this happens.’ And he threw all the little markers in a heap! We all laughed – but it was the Major’s way of saying tactics could be taken too far.”

Buckley was, though, a master of gamesmanship, determined to seek out any advantage he could. He had the Molineux pitch watered before games by the local fire brigade to give his younger, fitter sides the edge over older and more skilful teams.

The FA put a stop to that particular scam in 1939 – and also had to consider another of Buckley’s little ruses: his programme of injecting his players with extracts of monkey – and, later, ox – glands.

Monkey gland treatment was a fad introduced to Britain in the 1920s, by a Russian professor based in Paris. Winston Churchill, the Pope and Noel Coward were among the many and diverse adherents of the Voronoff method and, though its benefits

were unproven, the faddish, edgy Buckley became interested in it around 1935. Though the new ruse was considered, by turns, dodgy, damaging and hilarious by Wolves’ footballing rivals, the Major was dead set on it. One player, goalkeeper Don

Bilton, later recalled how his refusal to take a course of injections had effectively ended his career at Molineux.

On his first day at the club, Buckley told the young goalkeeper to report at 10 am the following morning for his jabs. Bilton’s father refused to grant his permission and the ensuing debate was “punctuated by astonishing combinations of swearwords…

The Major never forgave me, but it was a small price to pay for my well-being.”

While some regarded his attempts to squeeze the medical best out of his youngsters as eccentric whimsy – the Major claimed the injections actually made his players taller – others openly accused him of doping. In 1938 the FA set up an enquiry and

concluded, without banning the gland treatment, that individual players must decide for themselves what supplements they took. Whether those players could stand up to a Major dead set on administering the special medicine was another matter.

A second innovation – the team psychologist – was more a source of amusement than opposition: “On the manager’s instruction, I attended the psychologist’s surgery in Wolverhampton on some half a dozen occasions,” Stan Cullis said of his teenage

trips to the shrink. “So far as I could gather, he tried to build up my confidence through an analysis of my worries and problems, which, at this stage of my career, were not very many.”

Buckley’s general demeanour suggested no one had told him the war was over. Once when his team was staying at the same hotel as Manchester City, he noticed that City had a better team bus and ordered one of his assistants to commandeer the

vehicle for his own use. “Mention my name – Major Buckley,” he suggested, imperiously.

His military bearing ran through everything he did. One trainer who worked with Buckley was put in a quandary when one of the team’s players went down injured and the referee signalled for him to come on: Buckley, convinced his own player was

play-acting, would grab the trainer and forbid him to go onto the pitch just as the referee insisted he should come on. “I didn’t know whether to disobey the Major or the referee – or simply take the Major onto the pitch with me,” the hapless spongeman

later recalled.

While players scratched their heads and neutrals were divided over Buckley’s maverick methods and personal grooming style, Wolves fans of the 1930s were more divided over his buying and selling policy. True, it unearthed the players that helped

take the club into the top flight. But just as the club became one of the richest in the country as a result of Buckley’s wheeler-dealing, the team stalled in the lower reaches of Division One. Fans felt short-changed.

When Buckley came to Wolves, the club had an overdraft of £115,000 – a massive sum. Immediately, he set about selling the club’s most valuable players. By the late-’30s, Buckley had put the club firmly in the black and was making £25,000 a year on

transfers.

On the pitch, Wolves consolidated after their relegation-scrape of 1933 and the next three seasons of lower mid-table finishes saw fans getting restless with Buckley’s money-spinning selling policy. Once, the team bus was daubed with the slogan ‘Stop

Me and Buy One.’ Frustrations boiled over in November 1936 when, days after the sale of full-back Cyril Shaw, the club lost 2-1 at home to Chelsea. Over 2000 fans invaded the pitch, uprooted the posts, smashed the dressing-room windows and

called for Buckley’s resignation. The Major, ironically, was away on a scouting mission at the time. He was offered police protection on his return, but shooed it away. His ever-changing team quelled the unrest that season, in any case, breaking through

to finished fifth. The following season ,they were runners-up, losing out to the all-conquering Arsenal by a single point.

With the club at an all-time high, Buckley’s most lucrative – and controversial – deal was still to come. In 1938, the Major sensationally smashed the 20-year-old world transfer record by selling Bryn Jones – a former miner he had discovered playing for

Aberaman in south Wales – to Arsenal for £14,000. After five years under Buckley’s influence, Jones was the fans’ favourite and reckoned to be one of the best inside forwards in the world. Arsenal (and Spurs) had been courting him for two years when

the contract was finally signed.

In Wolverhampton, the departure of the local hero caused uproar. Three of the club’s self-professed ‘staunchest fans’ wrote a joint letter to the local paper.

“The directors’ thoughts would appear to run on the lines – ‘Why should we let our supporters have a decent team to watch, let’s make some money instead,’ ” it read.

Looking back over his career, Buckley denied he had ever run his teams for the benefit of the bank manager, though. “I have never transferred a player in my life just for the sake of money,” he once said. “When I have transferred a player, it has been

either in his own interest or because I have had someone better to take his place…”

Indeed, eight months after the bombshell sale of Jones to Arsenal, the Major’s team stood on the brink of an historic League and Cup double, having defeated their closest rivals for the title, Everton, 7-0 and pulled a still-record crowd of 63,315 to

Molineux for the Cup defeat of Liverpool.

The 1939 FA Cup Final would turn out to be the highpoint of Buckley’s managerial career. The team he had built was one of the youngest ever to play in a Cup Final and came to Wembley as red-hot favourites. Buckley was able to field his full-strength

first XI, a team that had never been beaten. He eschewed his customary plus-fours to meet the king, opting instead for a black suit, but it was the Portsmouth boss Jack Tinn (with his lucky spats), who would end up with his hands on the Cup. The

Buckley Babes looked nervous and sluggish and lost 4-1. The first goal was scored by Bert Barlow, sold by Buckley to Portsmouth weeks before. Wolves got their historic double – but it was the unwanted one of being the first side to finish second in

both league and Cup in the same season.

In the end, it was the war that did for the Major. This time round, he did not see active service (he volunteered in 1940, but being 57 at the time was turned down) and instead formed a Home Guard unit that did at last some of its training at Molineux. But

it did interrupt him just as his grand plan for Wolves was coming to fruition.

Wartime football was a thrown-together affair of guest players and youngsters, but the Major still left his mark. In 1942, his team won the wartime Cup, the only trophy the Major ever won. Buckley’s faith in youth saw him blood 16-, 15- and even

14-year-olds, sowing the seeds for post-War success. In the 1950s Wolves would win the league three times (and come second three times) with a manager, method and nucleus of a team all introduced by Buckley. By the time of that success, though,

the Major himself was long gone.

Buckley left Wolves in February 1944 in circumstances that have never been fully explained. Notts County had made their interest known in him early in December 1943, but the Major had publicly insisted he was not interested: County were a third

division team, Wolves were one of the biggest clubs in the country. But over the next two months, he changed his mind. Perhaps the reported £4500 salary was simply too much to resist, but Buckley was already the best paid manager in England. He

would never manage in the top flight again.

After Notts County, the Major spent two years at Hull, his scattergun approach to selection setting a new record as he used 43 players in the 1946/47 league season. Nonetheless, he put another promotion-winning team in place in next to no time –

before moving to Leeds, where he brought in the 16-year-old John Charles from Swansea and took Jack Charlton from the pit into the first team.

As at Wolves, Buckley took over a struggling, ageing side at Elland Road, brought in youngsters, made the club lots of money and foxed onlookers with his training methods: this time round, he brought dancers in to help with training and had the players

rubbed down with whisky on cold days. When Jack Charlton admitted he only had one pair of shoes, Buckley bought him a shiny new pair of brogues.When new boy John Charles told the Major he was a left-midfielder, the Major played him at right

full-back to make him two-footed and, in so doing, turned him into a world class centre-half and centre-forward. When Chelsea tried to buy Charles for a record £40,000, Buckley asked them for an imperious £100,000.

The Major moved to Walsall in 1953, another vertiginous drop down the divisions, another impossible challenge. This time, though, the prospects were even bleeker than they had been at the start of his previous assignments. Walsall were just about

the worst team in the league and had had to apply for re-election in the previous two seasons. With five weeks to go before the start of the 1953/54 season, the club had just 11 players on its books and no money to buy any more. Buckley tried

everything, plucking out improbable ex-pros from his contacts book and coaxing them back into the league, but by Christmas he had trialled 500 local players and admitted he was struggling. (One of his new signings was apparently so out of condition

that, when he fell over during his sole appearance for the club, he was unable to stand up again unaided). “The players are good fellows,” maintained Buckley. “They do their best – but we have to squeeze a little better than the best out of them.”

But the lack of resources mixed with Buckley’s own waning powers made Walsall a less than happy swansong. The side finished in the bottom four of the League in both Buckley’s seasons in charge. In 1956, with near-neighbours Wolverhampton

Wanderers arguably the best team in Europe, under the stewardship of Stan Cullis, the man who had set them both on the way retired from football. He died in December 1964.

The Major and his Wolverhampton Wanderers team stayed down in London after their shock defeat in the 1939 Cup final. On the Monday, they went to meet the Prime Minister. Neville Chamberlain, whose own career had only a matter of months to run,

commiserated with them on their defeat but suggested that, being a young side, they would no doubt have another chance. Major Buckley said that finishing runners-up in three tournaments in a row indicated there was “some little thing amiss” and

resolved to set up a committe of enquiry into the Cup final defeat. He would, he said, be the committee’s sole member.

Even with the front pages full of reports of speeches by Hitler and the RAF doing dummy flights over the countryside, the sports pages were still singing the praises of Buckley’s young team. “The Major can wait for his vintage wine to mature,” said

Daily Sketch football writer LV Manning. Wolverhampton’s own Star and Express was even more confident that the early 1940s would see glory days for Buckley’s side. ” Wolves supporters will be fully entitled to expect the club to go one better the next

time,” said its correspondent ‘Nomad’. “Already, Major Buckley is laying down his plans with the intention of bringing a major honour home next season.”

“There was nothing very friendly about him…”

Jimmy Dunn, who signed for Wolves in November 1942 and stayed for 10 years, recalls his time with Major Buckley